Contextual Intelligence: An Emerging Competency for Global Leaders

In the midst of globalization, emerging technology, global citizenship awareness and the advent of the global organization, the contextual environment in which leaders must operate is increasingly complex, even mind-boggling. Today’s business and organizational context is dynamic, turbulent, continuously evolving and requires innovative leadership. Like Israel, in the days of the sons of Issachar, there is a clarion call for leaders who can both diagnose the context they are in then exercise their knowledge to know what to do in the midst of changing and turbulent times. Quite literally, decisions must be instant, pragmatic and offer real solutions for real problems. Leaders who have the ability to contribute to these kinds of solutions, regardless of age or experience, are a valued commodity. These leaders have a high contextual intelligence.

Contextual intelligence is a leadership competency based on empirical research that integrates concepts of diagnosing context and exercising knowledge. Today’s leaders, managers, and employees must be able to foresee and diagnose any number of changing contexts quickly, then seamlessly adapt to that brand new context or risk becoming obsolete and irrelevant. Diagnosing context successfully requires intentional leadership and a paradoxical devotion to having a global perspective in the midst of local circumstances.

For business leaders to better appreciate contextual intelligence, it helps to understand the general concepts of context, intelligence, and experience. Context consists of all the external, internal, and interpersonal factors that contribute to the uniqueness of each situation and circumstance. Intelligence is the ability to transform data into useful information, information into knowledge, and then most importantly, assimilate that knowledge into practice.

Experience is measured by the ability to intuitively extract wisdom from different experiences and is not necessarily dependent on the accumulation or passage of time. In culminating these concepts, contextual intelligence consists of a specific skill set whereby an individual effectively diagnoses their context. It applies intelligence and experience, and is fundamentally about recognizing and interpreting the proverbial baggage people bring to the table, then determines how that baggage affects the current context and possible future. The contextually intelligent person then uses that new knowledge to exert influence in crafting a desirable future.

Diagnosing Context

Context is the background in which an event takes place. Contexts come in various forms and involve any set of circumstances surrounding an event. It is a rudimentary fact that knowing the specific context of an event is imperative to a correct interpretation. The context of an event or circumstance is much more involved than knowing the specific work setting, a geographic or demographic, or the mastery of technical competencies required of a given work setting.

Context is often real and perceived and includes such things as: geography, genders, industries, job roles or titles, attitudes, beliefs, values, politics, cultures, symbols, organizational climate, the past, the preferred future,band personal ethics. Compounding the difficulty of context is the growing need to recognize these contextual variables in self as well as in various external and internal stakeholders. The presence of these contextual variables and any number of other external or internal, overt or covert variables makes each context unique. These and other contextual variables come together to create the contextual ethos.

The implication of this is that the ability to diagnose context can become a leadership skill that transcends specific roles or environments. Context (such as background events, attitudes, and stakeholder values) is relevant. When context is approached with the intent to extract knowledge from it, the knowledge extracted is transferable to any different or future work setting. Contextual intelligence and the requisite skills have a high degree of transferability. The implication is that a contextually intelligent person can influence others regardless of their job setting or role.

The Intuitive Practitioner

“My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge,” (Hosea 4:6, NIV) is a commonly quoted scripture. Knowledge in this case is described as perception, discernment, or wisdom. This is not referring to the accumulation of or storing away of data or facts for later recall. The root word is yada, which means “to know.” Inherent to contextual intelligence is the use of intuition or to use a biblical phrase revelation.

Intuition is a unique application of experience. Traditionally, experience is described as the accumulation of time or a long history of related experiences. However, intuition as described of contextual intelligence is not dependent upon years of experience or the accumulation of time. As used to describe contextual intelligence, it involves being adept at instantly assimilating past events into the current context, irrespective of the context in which the original event occurred. It is “an innate ability to synthesize information quickly and effectively” note researchers Erik Dane and Michael Pratt.

For example, they note the accuracy of decisions decreases as more time is used in deciding suggesting that using intuition is a way to leverage this inverse relationship. Intuition also appears to be especially acute in turbulent environments. Therefore, since contextual intelligence involves diagnosing a dynamic context, intuition is an asset.

Furthermore, what you know and how you came about learning it (i.e., experience) is much less important than the ability to learn. Knowledge [intelligence] is not purely the result of theoretical propositions, analytic strategies, or in identifying the elements of the decision. In short, knowledge (or discovering the correct answer) is not always linear. In a contextually rich world 1+2 does not always = 3. Intuition (i.e., arriving at knowledge without rational thinking) often forms the basis for later intellectual exercises.

The business implication of this is that intelligence can be gained from interpreting different events and using intuition, and therefore, does not purely result from formal education, experience, or intellect. Experience results when preconceived notions and expectations are challenged, refined, or unconfirmed by the actual. Therefore, demonstrating appropriate behavior is the best indicator of experienced-based intelligence and not longevity or experience.

Aristotle wrote in Nicomeachean Ethics, that wisdom is an issue of maturity or, as he states, the “defect” of not having wisdom is from “living at the beck and call of passion.” Therefore, presumably wisdom itself is not necessarily a direct result of the passage of time or living per se, but is a result of coming to maturity. Because experience is so unique and individualized, it is difficult to use it as a learning model with any kind of predictive strength. Therefore, within the framework of contextual intelligence, experience can be measured by the amount of knowledge extracted from a single event.

The most intelligent people, the ones with the greatest business acumen or organizational savvy can extract the most knowledge from a single event, regardless if the event is positive or negative. Presumably, the newly acquired knowledge, when applied, is transformed into wisdom that can be “reused” in new context. Intelligence is certainly rooted in experience, but more importantly in the ability to extract valuable information about people, events, attitudes, behaviors, etc., from those experiences. The value and relevance of experience is measured by the magnitude of an individual’s contribution to values and goals. Experience is validated in the ability to contribute early and often in a new environment.

For example, a leader may have one year of experience, but that year could be significantly bolstered by myriad, meaningful experiences that significantly influence his or her practice of leadership. Based on the ability to extract wisdom from a single experience, one year may be equivalent to four or five years. That phenomenon is what I like to refer to as “experience in dog-years.” Therefore, the description of novice and expert must not be solely set by age or even number of past experiences per se, but “experience” should be evaluated in light of significant contributions. In this respect, experience is best defined by the leader’s ability to effectively use history in making decisions, even if the individual has a very limited history (i.e., experience). A meaningful history can be gained from personal experience, but also from the observation and study of others past and present. The contextually intelligent practitioner is able to extract lessons from a single experience, versus the less contextually intelligent person who requires multiple experiences before learning the same or similar lessons.

Contextual Intelligence

Considering the above descriptions of context, intelligence and experience, contextual intelligence is the ability to quickly and intuitively recognize and diagnose the dynamic contextual variables inherent in an event or circumstance and results in intentional adjustment of behavior in order to exert appropriate influence in that context.

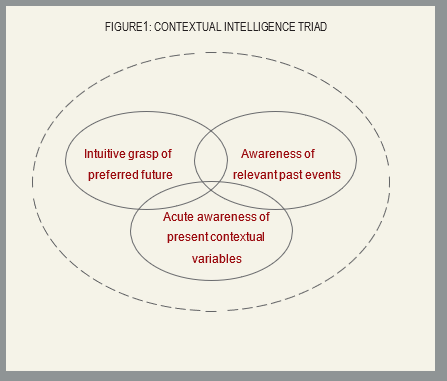

The contextually intelligent practitioner is knowledgeable about how to do something (i.e., has technical knowledge from formal education and observation), but more importantly is wise enough, based on intuition and experience, to know what to do. Knowing how to do can put someone in a position to influence and often is the result of formal education and traditional applications of experience. Knowing what to do keeps one in the place of influence and is a result of an intuitive awareness of past, present, and future. Knowing what to do, as opposed to knowing how to do something enables an individual to act appropriately in a context of uncertainty and ambiguity where cause and effect are not predictable. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the contextual intelligence triad. The three interlocking circles represent the relationship of the three elements of contextual intelligence that work together within a contextual ethos (dotted line).

Awareness of the contextual ethos involves being able to discern and accurately detect the attitudes, motivations, and values of many or all of the people who have a stake in the current situation. Awareness of the relevant history involves being able to reconcile the outcomes of past events and decisions into information that can be leveraged for the preset context and for future position. Awareness of the preferred future involves an acute understanding and vision of the future. It is an innate understanding that an individual’s present circumstances are not a result of the accumulation of past decisions. Rather, the current context is also a product of the intended or preferred future.

Practical Implications

The concept of contextual intelligence has far reaching implications, and may help explain what happens (or what is missing) when, in one context a leader flourishes, but that same leader, when promoted, transferred, or transitioned into another context, is not as successful.

Furthermore, it may also help practitioners and scholars develop training programs that teach leadership skill sets that transcend a specific context, and that has tangible value to any organization regardless of their uniqueness.

From a biblical framework, contextual intelligence has multiple applications. Consider the sons of Issachar. “From the tribe of Issachar, there were 200 leaders of the tribe with their relatives. All these men understood the signs of the times and knew the best course for Israel to take” (I Chronicles 12:32).

The sons of Issachar are potent examples of how contextual intelligence is supposed to operate in a changing world or in turbulent environments. They had two very distinguishing abilities, which presumably were the hallmark of their qualification to lead and direct Israel. Those qualities were: understanding the times (akin to “diagnosing context”) and knowing what to do (i.e., application of knowledge).

These two abilities, when used in tandem, can be powerful leadership tools. Tools, when applied in the context of past and future events, can transcend roles, positions, and titles, and can influence the carrier of these tools in whatever context they are found. Therefore, leadership can be exercised by the contextually intelligent practitioner in any setting or in any role.

Conclusion

Contextual intelligence has merit in that it warrants discussions on how the practice of leadership can and should

transcend context. Business leaders who exercise contextual intelligence are able to assimilate, cognitively and intuitively, past and current events in light of the preferred future. They think and act quickly when the circumstances and events surrounding their context change. They tend to intentionally lead by always seeking to be empathetic and scanning the horizon for value that can be used instantly and in the future.

Contextually intelligent leaders are multi- tasking thinkers who routinely go outside of their existing context to acquire useful information about the world in which they live and integrate that information into their decision making. In light of the potential contextual intelligence has as a leadership competency, there is much dialogue and work to be done toward validating contextual intelligence as a transferable construct for effectual leadership in global business.

| FIGURE 2: BEHAVIORS, SKILLS, AND BRIEF DESCRIPTORS ASSOCIATED WITH CONTEXTUAL INTELLIGENCE. | |

| Future Minded | Has a forward-looking mentality and sense of direction and concern for where the organization should be in the future. |

| Influencer | Uses interpersonal skills to ethically and non-coercively affect the actions and decisions of others. |

| Ensures an Awareness of Mission | Understands and communicates how the individual performance of others influences subordinate’s, peer’s, and supervisor’s perception of how the mission is being accomplished. |

| Socially Responsible | Expresses concern about social trends and issues (encourages legislation and policy when appropriate) and volunteers in social and community activities. |

| Cultural Sensitivity | Promotes diversity in multiple contexts and aligns diverse individuals by creating and facilitating diversity and provides opportunities for diverse members to interact in non-discriminatory manner. |

| Multicultural Leadership | Can influence and affect the behaviors and attitudes of peers and subordinates in an ethnically diverse context. |

| Diagnoses Context | Knows how to appropriately interpret and react to changing and volatile surroundings. |

| Change Agent | Has the courage to raise difficult and challenging questions that others may perceive as a threat to the status quo. Proactive rather than reactive in rising to challenges, leading, participating in, or making change (i.e., assessing, initiating, researching, planning, constructing, and advocating). |

| Effective and Constructive use of Influence | Uses interpersonal skills, personal power, and influence to constructively and effectively, affect the behavior and decisions of others. Demonstrates the effective use of different types of power in developing a powerful image. |

| Intentional Leadership | Assess and evaluates own leadership performance and is aware of strengths and weaknesses. Takes intentional action toward continuous improvement of leadership ability. Has an action guide and delineated goals for achieving personal best. |

| Critical Thinker | Cognitive ability to make connections, integrate, and make practical application of different actions, opinions, and information |

| Consensus Builder | Exhibits interpersonal skill and convinces other people to see the common good or a different point of view for the sake of the organizational mission or values by using listening skills, managing conflict, and creating win-win situations. |

Matthew R. Kutz, Ph.D., ATC, LAT, CSCS is assistant professor of Athletic Training & Clinic Management in the School of Human Movement, Sport, and Leisure Studies at Bowling Green State University. He also serves as Director of Clinical Education in the ATCM program there. Formerly with Texas State University, Dr. Kutz earned his Ph.D. in Global Leadership. His professional and scholarly interests include human performance, leadership competency and development, and innovation and change strategies. Dr. Kutz can be reached for comment via e-mail at mkutz@bgsu.edu.

Notes

- Aristotle. (1998). Nicomachean Ethics. London: Dover.

- Concepts on intuition were referenced from: Dane, E. & Pratt, M. (2007). Exploring intuition and its role in managerial decision making. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 33-54.

Isaack, T. (1978, October). Intuition: An ignored dimension of management. Academy of Management Re- view, 917-922.

Khatri, N. & Ng, H. A. (2000). The role of intuition in strategic decision making. Human Relations, 53: 57–86. - Discussion on knowledge and learning models in leadership are found in: Benner, P. (2001). From Novice to Expert. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Grint, K. (2007). Learning to lead: Can Aristotle help us find the road to wisdom. Leadership, 3(2), 231-246.