The Impact of Leadership Development Using Coaching

Organizational leaders must be clear about the value different leadership development options afford and the likely impact of each. As such, this paper will address three different leadership development options— self-directed, management-prompted, and coaching and then specify the likely return on investment organizational leaders can expect. In addition, it will go into greater detail regarding how leadership development programs that include coaching bring value to the individual and the organization, provided organizations are ready to align their program with business strategies, human resource initiatives, and client commitment.

Corporations, both in the United States (US) and abroad are recognizing that leaders are instrumental in managing change, innovating, and buffering the effects of environmental forces. Such leaders must possess idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual finesse, and an ability to connect immediate tasks to a larger vision. With such a list of demanding attributes and abilities organizations are certain to have a hard time finding and attracting these leaders.

Combine this list with talent pools that are shrinking in the areas of math, engineering, technology, and science and organizational leaders will find that they must do more than simply improve their hiring practices (Rothwell, 2010). Even as they begin to focus on employee retention using inclusion techniques, communicating a welcoming corporate culture, and offering a better benefits package, organizations will struggle to match existing talent with their needs (CSRA, 2018). Many industry giants like Chick-fila, Campbell’s Soup, Booz Allan Hamilton, UPS, and Whirlpool have already undertaken measures to develop their talent in-house, thereby signifying a major shift regarding what is needed to sustain a business.

Methods organizational leaders can employ to develop their people include self-direction, management-prompted, and coaching. Leave a person to self-instruct and only so much will happen. Add a trainer or mentor as part of an employee’s annual performance review and the individual is likely to achieve more. Engage a client with a leadership coach and transformation becomes more likely (Stoltzfus, 2005).

Yet, Shelton (2012) found coaching needed to be nested with a larger organizational program. The best leadership programs were those that used effective designs, engaged a diverse audience, and allowed for varied access and delivery (Shelton, 2012). Other experts have contended that at some point these programs must leap a generalized training approach to a context-specific one (Alan & Whybrow, 2008). With different options to consider, leaders must be clear about the value each leadership option offers and its impact. As such, this paper will address three different options— self-directed, management-prompted, and coaching and then specify the likely return on investment organizational leaders can expect.

What Should an Organization Hope to Achieve?

Leadership development is intended to close the gap between what leaders already know and what they need to know (VanVelsor, McCauley, & Ruderman, 2010). Collins (2002) highlighted that development requires a whole-person approach; and, Anderson and Anderson (2005) brought forward that development must occur within an organizational context. Summarily, development then includes skill, character, comportment, and inner personal alignment, in addition to leader-organizational alignment. Whereas employees enter the organization with varying levels of skill, experience, and character development, organizational leaders must determine to what extent they will enable their followers to grow and develop and how other business decisions will impact their leadership development initiatives.

Self-Directed Development

Many organizations employ a laissez-faire approach to leader and follower development. Employees are shown where to find corporate policies, benefits information (e.g., education reimbursement), online tutorials, and in some instances access to corporate “universities” (CSRA, 2017). Many of these corporate universities contain books, articles, and learning videos. Skillport from Skillsoft (2016), an education vendor, provides organizations a cloud-based repository of content, expertly produced to fit a specific audience’s attention and interest. They deliver the information using short videos and address topics to help the viewer improve communication, manage confrontation, and develop listening skills (Skillsoft, 2016). Challenges associated with this approach include:

- Followers not thinking they need to develop, as they often believe their current skills and position validate their competency (Skillsoft, 2016).

- Followers focusing on self-interest topics only. • Sources of information not aligning with corporate values, strategies, or objectives (Anderson & Anderson, 2005).

- An inability to ensure what employees learn and retain (Hunt & Weintraub, 2007).

Learning theories contend one must absorb, process, retain, and apply information as part of the learning process. Palmer and Whybrow (2008) proffered that learning is comprised of one’s cognitive, emotional, and experiential make-up and that one’s social and cultural identity influence the interpretation of new information. It is these aspects that impact how one translates information into usable knowledge and its application; thus, it is possible that followers who participate in selfdirected education may not grasp all the learning points accurately.

Organizational leaders that employe this approach, are likely to fair better than organizations that do not offer any leadership development options. Anderson and Anderson (2005) would suggest such an approach is not likely to proffer a measurable business impact. Meaning, what leaders currently observe or experience in the workforce regarding productivity, teamwork, and internal and external client satisfaction, is the full extent that this passive self-directed development method will produce.

Management-Prompted Development

Organizations that employ a management-prompted approach will likely experience varied results. Applications of this method include people managers prompting their followers to make use of existing educational benefits to obtain skill-based credentials; attain more advanced educational degrees with the hope of securing future promotions; and, engage in brief mentoring relationships to learn more about a specific knowledge area. In a manner, the mentoring approach is similar to what Hunt and Weintraub (2007) called “developmental coaching” as “the leader exists to increase the individual’s ability to perform a particular work role (or task)” (Hunt & Weintraub, 2007, p. 34). Stoltzfus (2005), similarly defined this type of interaction, as a method of teaching based on a mentor’s experience only.

Whereas management-prompted development may offer more of an opportunity for a follower to learn than the self-directed method, typically the learning is oriented toward achieving a skill. What is missing is the interaction one needs to generate self-awareness, which according to Perls (1969) is vital for retaining and applying new information (Perls, 1969).

As previously stated, this approach is likely to proffer better results at the technical level, as it enables people to enact business processes more accurately or with greater proficiency specific to the technical skill or knowledge area. What is unknown is the extent to which this approach imparts real business value; meaning, the value in terms of gaining client trust, offering repeatable quality to clients, and enhancing employee retention.

Leadership Development Using Coaching

Whereas the self-directed and management-prompted approaches are of some benefit, leadership coaching is more likely to translate into measurable forms of business value. Anderson and Anderson (2005) contended that coaching encourages clients to deepen their insights and translate those insights into action. According to Collins (2002), Palmer and Whybrow (2008), and Hunt and Weintraub (2007), coaching holds the promise of transformation, as it is the only method that inclines one to grow beyond surface issues. This is possibly due to what Lewis-Duarte (2012) found, describing how executive coaches use specific tactics to gain client commitment that changes behavior. These tactics included “gaining initial influence via consultation, the use of coalition tactics, inspirational appeals, and rational persuasion” (Lewis-Duarte, 2012, p. 255). Thus, by being in a coaching relationship, leaders can address their specific development needs and learn through the coaching experience regarding how to gain similar commitment from their followers.

Although coaching is believed to be the most effective form of leadership development, organizational leaders seeking to employ this method must establish appropriate expectations regarding what it can accomplish. For example, individual coaching programs are comprised of formal assessments, challenges, and support (VanVelsor, Mccauley, & Ruderman, 2010); but, they are not always connected to a challenging assignment, which is where the individual would apply their new-found leadership practice. In addition, some coaching programs may not be aligned with organizational strategies, thereby resulting in a direct benefit to the individual, but, not the organization.

Anderson and Anderson (2005) suggested leadership programs that translate coaching benefits into organizational value are those that emanate a “coaching culture” where everyone is in a preferred state of growing and developing. They suggested such a culture will not only help followers transform their insights into action, but will

- Increase productivity

- Improve teamwork

- Increase team member satisfaction

- Increase client satisfaction

Although leadership development within an organization helps everyone, many organizational leaders still retain an expectation mismatch. They believe coaching on its own will increase business development, retain talent, accelerate promotions, and increase diversity (Anderson & Anderson, 2005). Although these aspects are possible, such is not the case for all who engage in leadership coaching (Anderson & Anderson, 2005).

What is known, is that within the coaching-client relationship, clients develop in relation to the level of trust they perceive they have with their coach. Florin (2015) proposed as the coaching relationship moves from a task-role orientation toward a goal-action-results orientation and then an accountability orientation, leaders experienced a convergence between ideas, values, and responses making transformation possible. This is because, as Stainer (2016) contended, within the coaching context, the client experiences powerful questions, introspection, increased readiness, and needed space to re-frame their perspective. Still, it is possible for organizational leaders to get the wrong impression regarding how coaching can serve them. Meaning, one might think that “as a client learns new skills, such as a way of approaching challenges, and, merges this with an internal practice of knowing how to learn, an individual can self-reflect and gain meaningful insight without a coach” (Anderson & Anderson, 2005, p. 18). Although this is possible, most individuals will not likely push themselves, or dig deep, nor do they naturally continue to find ways to improve.

Leadership Development Programs

Hunt and Weintraub (2007) found the best leadership coaching experiences were those that were part of a broader development program. Such programs, as specified by Anderson and Anderson (2005) were those where

- Companies had dedicated staff to support coaching initiatives.

- Coaching was linked to the organization’s business strategies, human resource policies, and benefits package.

- Coaching was integrated with other leadership development approaches.

- Coaches were external to the organization to maintain confidence and reduce vulnerability.

- Individuals desired to change and were committed to the client-coach relationship.

When leadership coaching existed within this context both the individual and organization benefited (Anderson & Anderson, 2005).

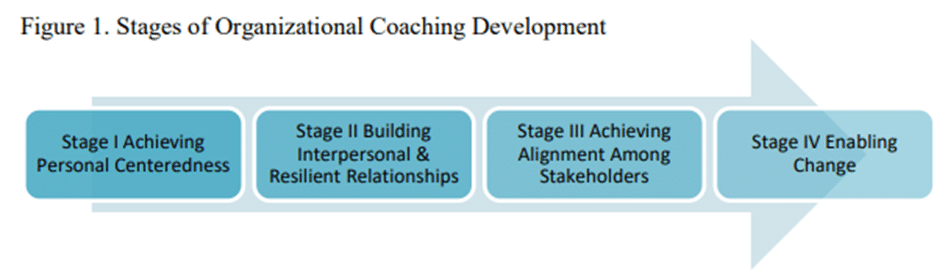

What is rarely considered is the value that coaching produces as client’s progress through the four stages of organizational coaching—Stage I gaining personal centeredness, Stage II building interpersonal and resilient relationships, Stage III creating alignment among teams, groups, or networks, and Stage IV enabling change at the individual and system-wide levels (Anderson & Anderson, 2005). See Figure 1.

Anderson and Anderson (2005) reported, for organizations that helped their leaders gain personal and professional focus there was a “$4.4K” return (Anderson & Anderson, 2005, p. 263). For leaders that developed an ability to build effective interpersonal relationships, a “$51.5K” was possible (Anderson & Anderson, 2005, p. 263). Leaders that were able to create alignment with internal and external stakeholders resulted in a “$83.5K” return and leaders that were able to generate change proffered a “$138.3K” return (Anderson & Anderson, 2005, p. 263).

Berg (2013) clarified the value of coaching by reporting what happens when leaders do not possess these abilities, specifically when they are in project manager positions. He contended for project managers that perceived their work experience as meaningful, this type of work provided an opportunity to learn continually, adapt, and find solutions (Berg, 2012). For those that perceived their position as too demanding, challenging, difficult, and stressful, often project tasks went unfulfilled. The outcome of which included a lack of client trust, diminished internal and external relationships, and minimal follow-on work.

Crane (2002) further defined the impact identifying the traits of a high-performance coaching-culture. He proffered, such cultures were “where people of character lived out their values within an organization that was aligned to accomplish their mission” (Crane, 2002, p. 195). Such cultures were those where (Crane, 2002, p. 195-196) Stage I Achieving Personal Centeredness Stage II Building Interpersonal & Resilient Relationships Stage III Achieving Alignment Among Stakeholders Stage IV Enabling Change

- Everyone in the organization knew the direction the organization was moving.

- Team members demonstrated a high sense of commitment to the organization, the team, and one another. • Communication among team members was extremely effective, promoting learning and forward action.

- The character of the organization was evidenced by follower behaviors that were congruent with the organization’s shared values.

- The organization and the individuals in it were open to and comfortable with change.

- A spirit of collaboration existed among the organization’s members.

- And coaching-like behavior was practiced up, down, and across the organization.

These traits translate into an organization’s ability to develop an internal directional system, a type of “internal gyroscope” that helped the organization’s people navigate through difficult circumstances (Crane, 2002, p. 196). Not only were goals and objectives clear, achievable, and well-coordinated; but, followers were able to report both success and failure (Crane, 2002).

The Tangible Benefits of Leadership Coaching

Leaders willing to nest coaching within a larger organizational development program should also be aware of the direct, tangible benefits associated with leadership coaching. These benefits include but are not limited to helping leaders develop emotional intelligence, establishing clear professional goals, and experimenting with new leadership practices when trying to institute change.

Coaching Helps Develop Emotional Intelligence

Considering organizational leaders gain more value when followers develop an ability to build interpersonal and resilient relationships (Stage II), Goleman (2008) proffered this is because truly effective leaders are those that possess a high degree of emotional intelligence. He defined emotional intelligence as being comprised of (1) self-awareness (i.e., understanding oneself), (2) empathy (i.e., understanding others), (3) self-management (i.e., being able to reflect and apply principles to oneself), and (4) relationship management (i.e., being able to collaborate with others). Thus, leaders able to develop their emotional intelligence and apply it to team interactions are more likely to understand situations that appear stressful and proactively take measures to cope or avoid negative outcomes. Further, such leaders will set more realistic expectations for him or herself and the team, which will ultimately reduce stress and harmonize team member interaction (Goleman, 2008).

Coaching Inclines Clients to Establish Clearer Goals

For clients wanting to develop an ability to create alignment with internal and external stakeholders (Stage III), coaching takes on greater significance. Anderson and Anderson (2005) reported that many clients do not naturally move toward this level, as this requires a leader to develop intuitive insight; thus, coach and leader can establish this as one of their professional goals. Florin (2015) opined coaches that brought together a leader’s “experiences, skills, and character within the coaching relationship prompt greater insight into the whole person, an aspect that accelerated permanent change” (Florin, 2015, p. 29). Kimsey-House, Kimsey-House, Sandahl, and Whitworth, (2011) further contended this is because the coaching-client relationship focuses on the leader’s desire for fulfillment, balance, and ability to practice new approaches when faced with different challenges. They defined each as

- Fulfillment occurs when a leader aligns their decisions with their values.

- Balance occurs when a leader can prioritize actions, manage expectations, and reframe their own perspective.

- Practice occurs when the client engages in an intentional discipline of exploring turbulence, issues, and challenges. Typically, this practice includes clarifying the issue, exploring it, experiencing the effects of the draft decision, identifying additional underlying issues, and then finding a new path forward.

The advantage of having “a safe and supportive space that allows the individual to express and explore fears and anxieties, results in one’s ability to formulate coping strategies and skills and test new approaches” (Kimsey-House et al., 2011, p. 155). Thus, without coaching, people are only likely to go so far in meeting their goals, as individuals typically avoid exploring triggers, underlying causes, assumptions, or reactions that keep them from progressing required attributes (Kimsey-House et al., 2011).

Coaching Enables Transformation

To become a leader able to create change (Stage IV) means one can identify opportunity in many different circumstances (Anderson & Anderson, 2005). Such a leader can change behavior in themselves and others by generating self-awareness, re-evaluating one’s perceptions, and then forming a new perspective when expected outcomes do not occur (Carey, Philippon, & Cummings, 2011). Vogus, Rothman, Sutcliffe, and Weick (2014) identified that highly reliable leaders are those who can balance high levels of doubt and hope simultaneously, as this is an indicator that one has “the capability to swiftly respond to the unexpected” (Vogus et al., 2014, p. 594).

Duncan (2014) summarized Campbell Soup’s CEO Douglas Conant’s experience, describing his ability to transform a corporation that was a mess in 2001. Having worked through a personal experience of being let go from a former organization, coaching helped Conant reformulate his perspective. This ability helped him lead others. The tactics Conant employed included staying on message, delivering on promises, and walking throughout the organization as a method of engaging others in idea development. Regularly, Conant followed-up his walking approach by writing multiple personal notes, acknowledging each individual’s contribution. “With a heart that communicated others mattered, he would listen, frame, and advance the organization’s strategies” (Duncan, 2014, n.p.). “By 2009 the company was outperforming both the S&P Food Group and the S&P 500. Sales and earnings were on the upswing. Core businesses were flourishing. And employee engagement was at world-class levels. The company now had 17 people who were enthusiastically engaged for every individual who was not” (Duncan, 2014, n.p.).

This type of change occurs because transformational leaders connect with their followers. Crane (2002) substantiated that 80% of feedback must be positive and 20% filled with constructive ideas for improvements, which was something Conant employed. Using coaching techniques, Conant would ask the question “How can I help?”, which was the same way his coach interacted with him when he was at the lowest point in his professional life (Duncan, 2014, n.p.).

Limitations

Despite all the benefits of coaching, Anderson and Anderson (2005) reported few clients matriculate beyond Stage II. This means 70% of the investment embedded in Stage III and IV are never realized (Anderson & Anderson, 2005, p. 251). Also, they also found the impact of coaching on business outcomes increased as the coaching relationship evolved. Meaning, “people who experienced the least number of hours of coaching correspondingly reported that coaching was less effective than clients who engaged in coaching for longer periods, as they reported it was tremendously effective” (Anderson & Anderson, 2005, p. 253).

As a result, organizational leaders must realize the success of leadership development programs is multifaceted. It is dependent on the alignment of organizational strategies and leadership development objectives, the use of credible and well-matched coaches, and the level of commitment of those being coached (Anderson & Anderson, 2005). This is because “transformation is strengthened when individuals and organizations are focused and committed to change and their reasoning is based on a knowledge of how consequences will impact behavior” (Carey, 2011, p. 51).

Call to Action

Based on these findings, organizational leaders may conclude leadership development is comprised of a 30% – 30% – 40% relationship between organizational alignment and culture, credible leadership programs and coaches, and individual client commitment to change. Before establishing an organizational program, leaders should assess their organization’s readiness. This requires determining if the existing business strategies and human resource policies align with the leadership development program objectives. Hunt and Weintraub (2007) provided a readiness assessment specific to four areas—”culture, business, human resources, and experience with coaching” (Hunt & Weintraub, 2007, p. 51-57).

Further, organizational leaders must determine the best leadership development approach and engage credible coaches. Whirlpool established a program that used an external leadership coaching consultant to develop a cadre of internal organizational coaches (Hunt & Weintraub, 2007). Other entities used external leadership coaches to support those at the executive level or those preparing for this level (Rothwell, 2010). Although leadership coaches are not specifically required to have credentials, those that adhere to established standards and practices, such as the International Coaching Federation (2017) Core Competencies, are more likely to be reputable. This is because, as Carey et al. (2011) found, the critical components of the coaching model includes—a robust understanding of the coach-client relationship, competency with problem identification, skills associated with goal-setting, and experience with having matriculated others through the transformation process.

| Action Steps |

| 1. ASSESS YOUR ORGANIZATION’S READINESS FROM A BUSINESS AND HUMAN RESOURCES PERSPECTIVE. |

| 2. DETERMINE THE BEST ORGANIZATIONAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAM APPROACH AND ENGAGE CREDIBLE COACHES. |

| 3. USE A PHASED COACHING APPROACH AND ASSESS THE INDIVIDUAL’S ABILITY TO GROW AND DEVELOP BEFORE ADVANCING TO THE NEXT STAGE. |

The final call to action includes assessing the individual’s level of commitment to the change process. Even though followers and the organization benefit from a Stage I level of coaching, an exponential level of growth and value occurs in Stage II, III, and IV. Different aspects of life, however, such as project constraints, life constraints, or one’s background or experience with coaching may present limitations. As such, organizational leaders may need to assess followers that are more prepared to explore their internal states of dissonance, as this type of work requires a great deal of introspection that many are not willing to undertake. Thus, organizational leaders may be best served by interviewing candidates or requesting their coaches to provide an assessment regarding an individual’s coach-ability.

Summary

With different leadership development options to consider, leaders must be clear about the value each option is likely to manifest. Organizations that offer a passive approach, using educational resources such as Skillsoft (Skillsoft, 2016), offer some benefit. Organizations that choose to build on their policies and benefits package to support educational endeavors will likely entice people to develop their skills in their respective field. Still, organizations that offer limited access to coaching will proffer a better return, as followers that develop professional focus commensurately improve their communication skills and ability to work within a team dynamic.

Considering, however, the greatest organizational value occurs when leaders develop an ability to build strong and resilient relationships, align internal and external stakeholders’ interests, and manage change, organizational leaders should be compelled now more than ever to support more advanced coaching initiatives. It is only within the coaching context that leaders are likely to develop these skills, due to the unique relationship the coaching-client relationship offers.

Despite these outcomes, coaching on its own will not translate to automatic business value unless the leadership development program is aligned with other business efforts. Organizations that choose to align their business strategies and human resource initiatives with their leadership development objectives are more likely to cultivate an organizational culture that will positively impact both the individual and the organization. Thus, when organizational leaders employ a comprehensive leadership development approach, everyone in the organization will experience a positive return.

About the Author

Cynthia S. Gavin is a strategist, having a diverse leadership background in healthcare, disaster response, and U.S. military planning. Among her favorite positions, Ms. Gavin has provided strategic advisement for the U.S. Secret Service’s Technical Security Division, The City of New York Office of Emergency Management, and the U.S. Army Edgewood Chemical Biological Center. Presently she is an advisor to the Assistant Secretary of the Army, Manpower and Reserve Affairs Division. Ms. Gavin holds a Master of Science in Emergency Health Services Planning, Policy, and Administration and is becoming a Doctor of Strategic Leadership at Regent University. Questions or comments regarding this article may be directed to the author at: Cynthia Gavin at: cyntgav@mail.regent.edu.

References

Anderson, D. & Anderson, M. (2005). Coaching That Counts Harnessing the Power of Leadership Coaching to Deliver Strategic Value. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Berg, M., & Karisen, J. (2013). Managing Stress in Projects Using Coaching Leadership Tools. Engineering Management Journal, 52-61.

Campbell Soup. (2017). University Recruiting. Retrieved from Cambell’s Career Center: http://careers.campbellsoupcompany.com/university-recruiting/

Carey, W. P. (2011). Coaching Models For Leadership Development: An Integrative Review. Journal of Leadership Studies, 51-69.

Crane, T. (2002). The Heart of Coaching: Using Transformational Coaching To Create A High-Performance Coaching Culture, Second Edition. San Diego: FTA Press.

CSRA. (2016, June 11). CSRA. Retrieved from csra.com: http://csra.com/

Duncan, R. (2014, September 18). How Campbell’s Soup’s Former CEO Turned the Company Around. Retrieved from Fast Company: https://www.fastcompany.com/3035830/howcampbells-soups-former-ceo-turned-the-company-around

Florin, W. (2015). Creating Change Faster: Convergence and Transformation Acceleration. Journal of Practical Consulting, 29-37.

Guan, M. & So, J. (2016). Influence of social identity on self-efficacy beliefs through perceived social support: A Social Identity Theory perspective. Communication Studies, 588-604.

Hunt, J. & Weintraub, J. (2007). The Coaching Organization A Strategy for Developing Leaders. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

ICF. (2017, November 11). Core Competencies. Retrieved from International Coach Federation: https://coachfederation.org/credential/landing.cfm?ItemNumber=2206&navItemNumber =576

Kimsey-House, H., Kimsey-House, K., Sandahl, P. & Whitworth, L. (2011). Co-Active Coaching Changing Business Transforming Lives, Third Edition. Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Lewis-Duarte, M., & Bligh, M. (2012). Agents of “influence”: exploring the usage, timing, and outcomes of executive coaching tactics. Leadership & Organizational Development Journal, 255-282.

Palmer, S, & Whybrow, A. (2008). Handbook of Coaching Psychology A Guide for Practitioners. East Sussex: Routledge.

Perls, F. (1969). Gestalt Therapy Verbatim. Moab: Real People Press.

Reyes Liske, J., & Holladay, C. (2016). Evaluating coaching’s effect: competencies, career mobility, and retention. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 936-949.

Rothwell, W. (2010). Effective Succession Planning: Ensuring Leadership Continuity and Building Talent from Within, 4th ed. New York: AMACOM.

Shelton, K. (2012). Leadership Excellence: 2012 Leadership 500. www.LeaderExcel.com.

Skillsoft. (2016). Skillport Platform. Retrieved from Skillsoft: http://skillport.com/

Stanier, M. (2016). The Coaching Habit Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead Forever. Toronto: Box of Crayons Press.

Stoltzfus, F. (2005). Leadership Coaching The Disciplines, Skills and Heart of a Christian Coach. Virginia Beach: Tony Stoltzfus.

Vogus, T., Rothman, N., Sutcliffe, K. & Weick, K. (2014). The Effective foundations of high-reliability organizing. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 592-598.