Empowering Stewardship: Leadership Lessons from Exodus 18:13-27

Moses presents an excellent model for the study of biblical servant leadership in the Old

Testament and exemplified many of the qualities of modern servant leadership theories deem

essential such as compassion, humility, altruism, stewardship and service of others (Patterson,

2003; Patterson & van Dierendonck, 2015). Although far from perfect, there are ample stories

from Moses’ life that point to the motivations and virtues of his leadership (notions of being) as

well as the antecedents and outcomes of Moses’ behavior as a leader. This exegetical analysis

of Exodus 18:13-27 furthers the study of biblical servant leadership by examining the necessary

connection between a servant leader’s motivation to “serve first” and the overflow of that desire

into action that empowers others. By examining servant leadership through the lens of biblical

narrative, a rich picture of leadership emerges as Moses demonstrates how important

stewardship and empowering others is to the optimal functioning of a community and

organization.

I. INTRODUCTION

Moses is often cited as a biblical example of servant leadership (Bell, 2014; Crowther, 2018, Boyer, 2019); he demonstrated a deep love for God and others, humility in his approach to God and his own abilities, and an impetus to serve God, and His chosen people. Robert Greenleaf, the oft-acknowledged father of modern servant leadership, argued that servant leadership is based on “the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first” (Northouse, 2016, p.226), while Patterson (2003) constructed the virtuous theory of servant leadership with a foundational principle of agapao love, a Greek word for moral and ethical love with strong connections to deep preference for others. Beginning with his initial calling (Exodus 3), through his role in the deliverance of Israel from slavery, and continuing to his leadership of the Israelites and the establishment of covenant between them and God, Moses exemplified many of the qualities outlined in modern servant leadership theories as essential: compassionate love (or agapao as mentioned above), humility, altruism, vision, trust, empowerment, authenticity, stewardship, and service among others (Patterson, 2003; Patterson & van Dierndonck, 2015). Moses was by no means perfect, but his close relationship with God allowed him to guide a rebellious nation of slaves into relationship, identity and purpose as the chosen people of God. There are ample stories of Moses life that point to the motivations and virtues of Moses’ leadership (concepts of being), however this exegetical analysis of Exodus 18:13-27 will focus on the outcomes of Moses’ behaviors as a servant leader: his empowerment of other leaders, stewardship of the people of God and his openness to input from others. Utilizing traditional exegetical analysis and social rhetorical interpretation methods to examine and unpack the biblical text, this paper will explore the various ways biblical leadership concepts provide texture and understanding to modern servant leadership theory.

II. EXEGETICAL ANALYSIS

This passage of scripture falls into the larger story of Israel’s escape from Egypt at a very interesting juncture; the nation of Israel had recently crossed the Red Sea and began their trek into the wilderness of Shur and God himself was providing for their daily needs. The chapters directly before the text in question narrate God’s miraculous provision of bread from heaven (Ch. 16), water from a rock in the desert, and deliverance from enemy armies (Ch.17). Chapter 18 opens with a visit to Moses by his father-in-law Jethro and the next morning, Jethro’s observation of a clear organizational problem as Moses meets with the people, hears disputes and makes decisions. Jethro, an experienced leader in his own right, has the opportunity to see Moses in his new leadership role and offer him some practical leadership advice.

Utilizing socio-rhetorical interpretation (SRI) and inner texture analysis is very helpful in this passage, giving initial insight into the text itself through an examination of the features of language and style. These include repetitive texture (where there is ongoing repetition of certain words or phrases), progressive texture (the author’s use of progressive sequences within the text—what happened first, second, third), narrational texture (what voices are used in the text—first person, third person, etc.—and whether there is a narrator or dialogue in the text), opening-middle-closure texture (a clear beginning, body and conclusion within the passage), argumentative texture (the inner reasoning and logical assertions within the text), and sensory-aesthetic texture (the range of senses that the language invokes) (Crowther, 2019). The narrative follows a familiar story arc, aptly called the transformative journey, which “features a protagonist who is relatable, a catalyst that compels the protagonist to act, obstacles, a turning point and a resolution resulting in lessons for the actor and, perhaps, the audience too” (Yost, Yoder, Chung & Voetmann, 2015). In this way, the passage can be broken into three sections for analysis and together form a natural opening-middle-closing for the passage as a whole: verses 13-15: Moses’ long day of hearing people’s issues and making decisions, Jethro’s initial inquiry and Moses’ response, verses 16-23: Jethro’s response and advice to Moses, and verses 24-27: Moses’ implementation of Jethro’s suggestions, the outcome and Jethro’s departure.

Exodus 18:13-15: The Problem

The first section of this pericope provides the context and tone for the rest of the passage. Moses spends the entire day dealing with the needs and concerns of the Israelite people (“from morning till evening” – v.13) and Jethro, whose “own experience as a Midianite leader may have involved him in regular judging among the Midianites” observes that “Moses had over committed his time to his judicial role” (Boyer, 2017, p.78). His father-in-law addresses a clear problem to Moses in the opening of this pericope, “What is this you are doing for the people? Why do you sit alone, and all the people stand around you from morning till evening?” It is clear that Jethro was not addressing Moses’ physical state (he was surrounded by people all day) but his metaphorical state within the context of leadership: Moses was alone in carrying the weight of responsibility and decision-making, and this was a clear problem.

In a display of argumentative inner texture, Moses responds to Jethro with an explanation that is based on a unique responsibility Moses does carry, his position as intermediary between the people and God. “The people come to me to inquire of God […] and I make them know the statutes of God and his laws” (v. 15, 16b). The reasoning that this texture demonstrates is related to Moses’ calling: something he alone could do before God. However, the argument in the middle of these two bookended statements was not a unique responsibility of Moses: “when they have a dispute, they come to me and I decide between on person and another” (v.16a). Jethro, exercising wisdom as an experienced leader, offers Moses a solution to the problem.

Exodus 18:16-23: The Solution

This section of the pericope is, in the context of narrational inner texture, composed entirely of Jethro’s suggestions to Moses, a monologue complete with the caveat, “I will give you advice, and God be with you” (v.19a)! Jetho’s advice has progressional inner texture and a beginning-middle-closing to his argument. The beginning, “what you are doing is not good, you will certainly wear yourself out, you are not able to do it alone,” followed by a separation of what Moses’ unique calling is before the Lord (“You shall represent the people before God” v.19b) and what he can do to empower other potential leaders (“look for able men […] and let them judge the people at all times, every great matter they shall bring to you but any small matter they shall decide themselves” v.22). Jethro’s advice closes with an encouragement to Moses of what God can do if he relinquishes control to others (“God will direct you, you will be able to endure and [there will be] peace” v.23). This section has several interesting facets:

- The use of repetitive inner texture in the first passage with the Hebrew word for ‘judge” (“Moses sat to judge,” “Why do you alone sit as judge?” “I judge between a man and his neighbor”) and it’s contrast in this section (“Let them judge,” “every minor dispute they will judge”). Shaphat (to judge, govern or rule) is used as a signal for the leadership first carried by Moses alone in the first passage, but that Jethro advocated sharing in the second passage and by the third passage (the resolution) Moses has successfully given to others (Brown, Driver, & Briggs, 1996).

- The character qualities advocated by Jethro in looking for leaders were that they be able (capable, strong), fear God (have humility and understand followership), be trustworthy (honest) and be above bribery (have integrity) so that Moses could share the weight of leadership with them (“it will be easier for you, and they will bear the burden with you” v.22b).

- Jethro encourages Moses that if he relinquishes control to others, he will “be able to endure” – the Hebrew word for endure, `amad, can be translated to stand, to remain, to establish, to give stability but also is translated 12x in the Old Testament as a form to the word “to serve,” depending on context (serve, served, serves service, serving) (Brown, Driver, & Briggs, 1996). It is an interesting thought exercise to consider the texture and nuance that provides: “God will direct you, you will be able to endure-serve-stand-remain-establish-give stability and all this people will also go to their place in peace” (v.23).

Exodus 18:24-27: The Resolution

In the closing passage of this pericope, Moses implements Jethro’s advice, listening “to the voice of his father-in-law” and installing “able men” as leaders among the people. The new leaders, “judged the people at all times. Any hard case they brought to Moses, but any smaller matter they decided themselves” (v.26). Campbell (2006) remarks, “this an important passage, [because it shows that] Moses, with his great responsibility to lead, is not averse to being led; with his great task of teaching, he is not unwilling to learn” (p.74). In his willingness to follow his father-in-law’s lead, Moses made decisions that would ultimately “leave most of Moses’ time free of judicial responsibilities for him to lead the people in other ways, including his ministry of prayer and worship and his ministry of teaching and preaching all God’s laws” (Stuart, 2006).

III. MOSES AND SERVANT LEADERSHIP THEORY

This passage of scripture is full of leadership lessons for both inexperienced and practiced leaders. The lessons learned from Moses’ example can be summed up in an examination of the argumentative inner texture of this text (the inner reasoning or logical assertions within the text – namely the major and minor premises followed by the conclusion):

- Major Premise: Do not attempt to do leadership by yourself and carry the burden of ministry alone; where it possible, delegate! You were not designed to be a one-man show and will not be able to bear the burden of sole responsibility and control.

- Minor Premise: Find men and women of character to delegate leadership to; pay attention to their capacity and abilities, character (namely humility and integrity), motivations, and who or what they follow (i.e. are they submitted to others? Following God? Only interesting in themselves?).

- Conclusion: God will direct you, you will have the capacity to endure and serve faithfully, and their will be peace among you followers.

Gotsis and Grimani (2015) argue that inclusive leadership —as exemplified in the advice of Jethro and follow-through of Moses to empower other leaders— “is centered on empowering employees” and “bears potential for new ways of relating, sense making and creativity;” it is “a relational construct that expands on care compassion skills to account for prompt responses to fluid environments, in view of fostering deeper relationships, modeling courage and embracing a profound sense of humanity” (p.989). This connects to servant leadership’s aim to “serve followers while developing employees to their fullest potential in different areas such as task effectiveness, community stewardship, self-motivation , and also the development of their leadership capabilities” (van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2015, p.119). Although Jethro did not have a formal leader-follower relationship with Moses, he exercised servant leadership in helping to develop Moses to his fullest potential by addressing his task effectiveness, community stewardship and leadership capabilities and simultaneously “providing vision, gaining credibility and trust from followers and influencing others by focusing on bringing out the best” in Moses (van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2015, p.119)

This passage of scripture also challenges leaders, experienced and inexperienced alike, to consider what responsibilities of leadership pertain to calling (such as Moses’ calling to represent the people before the Lord and teach them His ways as He revealed Himself to Moses) and the “glass balls” that only they can juggle, and what responsibilities have the potential to be “rubber balls” that can be given to another to foster empowerment, inclusivity and creativity. As in the case of Moses, often it might take a wiser, more experienced leader to point out the differences in the weights of responsibility we carry, what burdens can be put down, what can transferred to someone else and what is unique to calling and divine purpose.

IV. CONCLUSION

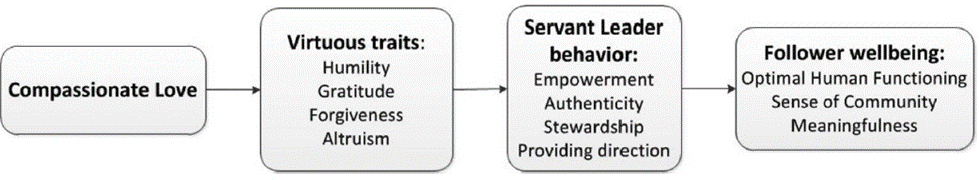

This pericope of scripture presents a set of important lessons that can be applied to servant leadership theory as a whole. While much of servant leadership theory is centered on inner motivation, care for others and an innate desire to serve, namely the being side to servant leadership, there is also the action oriented, behavioral (doing) side of servant leadership as well. Just as “faith by itself, if it does not have works, is dead” (James 2:17), it stands to reason that inner realities of love, humility, gratitude, forgiveness and altruism, if not accompanied by the actions associated with trust, vision and self-sacrifice, and without empowerment, authenticity and stewardship, would have little power to transform and influence others. As van Dierendonck and Patterson (2015) propose, it is a foundation of love that gives birth to the virtuous traits of servant leadership (Patterson, 2003), and combines with servant leadership behaviors that leads to a sense of follower wellbeing.

The leadership stories of Moses demonstrate the full scope of biblical servant leadership: the essential nature of underlying motivation and virtue as well as the expression of that motivation and virtue in behavior and substantive outcome. Activating others through empowerment and stewardship is essential to the optimal functioning of the greater community. Every piece of the servant leadership puzzle is needed to see transformation.

About the Author

A graduate student of organizational leadership at Regent University, Cassi is passionate about connecting biblical leadership principles with modern leadership theory and applying them everyday situations. Her leadership experience in both ministry and secular settings has taught her first-hand how crucial healthy leadership is to the success of any group, large or small. Currently, Cassi is creating leadership training materials for her local church, crafting a small group curriculum that will allow believers to be trained and empowered to maximize the gifts God has given them, meaningfully engage with others and influence their community for Christ.

About Regent

Founded in 1978, Regent University is America’s premier Christian university with more than 11,000 students studying on its 70-acre campus in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and online around the world. The university offers associate, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in more than 150 areas of study including business, communication and the arts, counseling, cybersecurity, divinity, education, government, law, leadership, nursing, healthcare, and psychology. Regent University is ranked the #1 Best Accredited Online College in the United States (Study.com, 2020), the #1 Safest College Campus in Virginia (YourLocalSecurity, 2021), and the #1 Best Online Bachelor’s Program in Virginia for 10 years in a row (U.S. News & World Report, 2022).The School of Business & Leadership is a Gold Winner – Best Business School and Best MBA Program by Coastal Virginia Magazine. The school also has earned a top-five ranking by U.S. News & World Report for its online MBA and online graduate business (non-MBA) programs. The school offers both online and on-campus degrees including Master of Business Administration, M.S. in Accounting (to include CPA Exam & Licensure Track), M.S. in Business Analytics, M.A. in Organizational Leadership, MA. in Product Management, Ph.D. in Organizational Leadership, and Doctor of Strategic Leadership.

References

Bell, S. (Ed.) (2014). Servants and Friends: A Biblical Theology of Leadership. Berrien Springs: MI: Andrews University Press.

Brown, F., Driver, S.R., & Briggs, C. (1996). Hebrew lexicon entry for Shaphat. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Hendrickson Publishers.

Brown, F., Driver, S.R., & Briggs, C. (1996). Hebrew lexicon entry for ‘Amad. The Brown-Driver-Briggs Hebrew and English Lexicon. Hendrickson Publishers.

Campbell, I.D. (2006). Opening up Exodus. Leominister, United Kingdom: Day One Publications. Accessed through the Logos Bible Software App for iOS.

Crowther, S.S. (2018). Biblical servant leadership: an exploration of leadership for the contemporary context. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Crowther, S.S. (2019) Innertexture analysis: From socio-rhetorical interpretation. Educational Powerpoint for LSDL773. Regent University.

Gotsis, G. & Grimani, K. (2016). The role of servant leadership in fostering inclusive organizations. Journal of Management Development. Vol. 35 (8). 985-1010.

Jaiswal, N.K. & Dhar, R.L. (2017). The influence of servant leadership, trust in leader and thriving on employee creativity. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal. Vol. 38 (1). 2-21.

Northouse, P.G. (2016) Leadership: Theory and practice. (7th. Ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Patterson, K. (2003) Servant leadership: A theoretical model. Servant Leadership Roundtable. Aug.

Sousa, M. & Van Dierendonck, D. (2015). Servant leadership and the effect of the interaction between humility, action and hierarchical power on follower engagement. Journal of Business Ethics. 141:13-25.

Stuart, D. K. (2006) Exodus: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. (New American Commentary, Vol. 2.). Nashville, TN: B&H Publishing Group. Accessed through the Logos Bible Software App for iOS.

Van Dierendonck, D. & Patterson, K. (2015). Compassionate love as a cornerstone of servant leadership: An integration of previous theorizing and research. Journal of Business Ethics. 128:119-131.

Yost, P.R., Yoder, M.P., Chung, H.H., & Voetmann, K.R. (2015). Narratives at work: Story arcs, themes, voice and lessons that shape organizational life. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research. 67(3). 169-188. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.regent.edu:2048/10.1037/cpb0000043