Sustainable Leadership Development: A Conceptual Model of a Cross-Cultural Blended Learning Program

This longitudinal cross-cultural case study demonstrates that sustainable leadership can evolve from

carefully orchestrated educational programs. Using a mixed-methods approach to study learners during a

two-year graduate program and two years post-graduation, this research confirmed that leadership

sustainability was an intricate weaving of multiple factors in three critical areas: (a) sustained

communication in the ICT/Blended environment, (b) sustained mentoring, and (c) sustained curriculum

and learning. In response to the research question—how do we enhance leadership sustainability in a

cross-cultural blended learning leadership education program—we found the synergy of sustained

educational and communicational elements to be key. Together, they immersed learners in a

virtual/blended learning environment that focused on ethics, values, and transformation at the personal

and organizational levels. Through modeling and mentoring, learners received intentional leadership

support while learning to build leadership sustainability within themselves and their followers. Such

learning creates a cycle of ongoing leadership development that continuously moves current and future

leaders from information to the creation of reservoirs of knowledge and wisdom, further deepening and

sustaining leadership. This continuous leadership growth provides an important constant in the evolution

of sustainability, demonstrating that like sustainable development, sustainable leadership represents a

process, not an end state.

Leadership’s role in sustaining corporate and societal change is well-documented by renown

experts such as Burt Nanus (1992) with his focus on visionary leadership, the late Peter Drucker

(1996) with his emphasis on leaders of the future, and Warren Bennis (1998) with his notion of

becoming a leader of leaders. Further reinforcing the leader‟s significance in sustainability,

Brady (2005) cited Burson-Marsteller‟s (2001) study conducted on the CEOs of the top 30

publicly traded companies in Germany, in which “the result suggested that the public

reputation of the company is to almost two-thirds determined by its leader” (p. 107). Confirming

this finding, a subsequent Burson-Marsteller study conducted in the U.S. “of 1155 key

stakeholders found that the reputation of the CEO contributes heavily to how companies are

perceived today” (as cited in Brady, p. 108). With a proclivity toward receiving ongoing

sustainability accolades, Brady noted that leaders at companies such as Ben and Jerry‟s (Ben

Cohen), BP (Lord Browne), DuPont (Chad Holliday), and Patagonia (Michael W. Crooke) have

made sustainability an organizational priority. But what is sustainability and how does it relate to

sustainable leadership development in global societies; and, most importantly for the work here,

does advanced education through modern technologies promote leadership sustainability across

and among cultures?

Sustainability and Sustainable Development

Driving sustainable development in the global environment, the UN resolution Agenda 21

called for the examination of four key areas: (a) social and economic dimensions (e.g.,

promoting health, combating poverty, and decision-making based upon environmental

development); (b) conservation and management of resources (e.g., combating pollution and

protecting forests and other fragile environments); (c) strengthening the role of major groups

(e.g., children, women, and workers); and (d) means of implementation (e.g., education and

technology) (UN Department of Economic & Social Affairs, 1992). One cannot combat poverty

or promote sustainable agriculture and rural development without sustainable leadership in

economic, educational, and civil realms. Nor can one strengthen the roles of children, workers,

farmers, business and industry, or the scientific and technological communities without

leadership that recognizes the need for an ongoing investment in the community. From these

initiatives, one thing is clear: a key element to the success of this agenda and the productive

advancement of society in this century is leadership, thus making sustainable leadership

development imperative.

One critical challenge is to define sustainability and its related concept, sustainable

development. Acknowledging a need for explicit definitions, Portney (2003) conceded that these

are often considered broad concepts with multiple meanings. Asserting that while sustainability

is often understood, Riddell (2004) concurred with Portney that it is not well-defined. In contrast,

Brady (2005) subsequently tackled the definitions. In his opinion, “sustainability refers to the

ability of something to keep going ad infinitum” (p. 7), and sustainable development “represents

a journey, not a destination” (p. 6).

Although some trace the genesis of the term sustainability to Lester Brown, an ardent

environmentalist and founder of Worldwatch Institute (Hargreaves & Fink, 2006), others identify

the 1987 Bruntland Report. Interwoven with sustainability, this report claimed that sustainable

development “implies meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of

future generations to meet their own needs” (United Nations General Assembly, 1987, ¶ 2). This

theme was reiterated in Agenda 21, emanating from the 1992 United Nations (UN) Conference

on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro (Earth Summit), and again at the UN 2002

Johannesburg Summit (Earth Summit 2).

Historically, the term sustainability is most often seen in the environmental and

ecology lexicons (e.g., Brandon & Lombardi, 2005); however, it more recently has been

embedded in economic development literature, particularly in the realm of sustainable cities

(Ling, 2005; Portney, 2003; Riddell, 2004; Sorensen, Marcotullio, & Grant, 2004). Beyond

economics and the environment, Brady (2005) found a sustainability emphasis in what he

classifies as “„hard-core‟ business journals” (p. 11). He went so far as to say that “corporate

sustainability could be set to represent the revolution of the twenty-first century . . . . [He further

claimed that] „smart companies‟ are trying to engage civil society, moving from being a part of

the problem to being part of the solution” (p. 12). This is in keeping with Fullan‟s (2005)

definition of sustainability: “the capacity of a system to engage in the complexities of continuous

improvement consistent with deep values of human purpose” (p. ix). To achieve this

sustainability, Fullan called attention to the role of leadership. He noted Archimedes, the first to

explain the principle of the lever. In Fullan‟s judgment, Archimedes pointed to a very important

element of sustainability when he said, “„Give me a lever long enough and I can change the

world.‟” Fullan further declared, “for sustainability, that lever is leadership” (p. 27).

Implying the importance of leaders to not only understanding organizational structures

but also ethics and morality, Fullan (2005) stressed that all levels of a system must take moral

purpose seriously in the sustainability process. In conjunction with this, the Sustainability

Leadership Institute (n.d.) teaches that “humanity has the ability to make development

sustainable” (¶ 3). Such institutes develop and increase leadership capacity locally, nationally,

and internationally to create economic, environmental, and social sustainability.

While a paucity of literature on leadership sustainability exists, one primary study

sponsored by the Spencer Foundation emphasized the importance of sustainable leadership. In

their three-decade study of educational change at eight Canadian high schools, Hargreaves and

Goodson (as cited in Hargreaves & Fink, 2003) indicated “that one of the key forces influencing

change or continuity in the long term is leadership, leadership sustainability” (p. 2). Furthering

this and embracing the environmental stance, Hargreaves and Fink claimed that sustainability is

more than merely making things last:

Sustainable leadership matters, spreads and lasts. It is a shared responsibility,

that does not unduly deplete human or financial resources, and that cares for and

avoids exerting negative damage on the surrounding educational and community

environment. Sustainable leadership has an activist engagement with the forces

that affect it, and builds an educational environment of organizational diversity

that promotes cross-fertilization of good ideas and successful practices in

communities of shared learning and development. (p. 3)

From this definition, Hargreaves and Fink specifically cited seven critical principles of sustained

leadership:

- Sustainable leadership creates and preserves sustaining learning.

- Sustainable leadership secures success over time.

- Sustainable leadership sustains the leadership of others.

- Sustainable leadership addresses issues of social justice.

- Sustainable leadership develops rather than depletes human and material

resources. - Sustainable leadership develops environmental diversity and capacity.

- Sustainable leadership undertakes activist engagement with the environment.

(pp. 3-10)

In 2004, Hargreaves and Fink reframed these seven principles into a more concise form:

sustainable leadership matters, spreads, lasts, is socially just, is resourceful, promotes diversity,

and is activist. Continuing the evolution of this concept in 2006, the authors promoted the depth,

length, and breadth of sustainable leadership while reinforcing justice, diversity, resourcefulness,

and conservation, which they clarified as learning “from the best of the past to create an even

better future” (p. 20). In fact, Hargreaves (2007) went so far as to say that sustainable leadership

“preserves and develops deep learning for all that spreads and lasts, in ways that do no harm to

and indeed create positive benefits for others around us, now and in the future” (p. 224). At the

core of these principles is the need for leadership education to encourage leaders to know

themselves, their gifts, and personality tendencies, as well as their leadership abilities within the

organization.

While meeting leaders where they are, developing today‟s leadership in a global society

demands an educational model that enhances leader sustainability. This begs the question that

became our foundational research inquiry: how do we enhance leadership sustainability in a

cross-cultural blended learning leadership education program?

Methods

Leadership sustainability is the ability of leaders to recognize the intricate systems

interwoven with human values that promote sustainability. Therefore, examination of a

successful leadership development program will provide insight regarding leadership education.

Using a mixed-methods approach, this study involved a longitudinal case study of a two-year

cross-cultural graduate-level leadership program. In addition, the researchers tracked these

participants for two years post- graduation (a) to determine the participants‟ leadership

sustainability and (b) to assess program quality in sustaining leadership development.

The Program

The selected program emphasized leadership transformation and ethics, consistent with

Hargreaves and Fink‟s (2003, 2004, 2006) concern for social justice and Fullan‟s (2005) concern

for the moral underpinnings required for sustainable leadership development. It also reflected the

complexity of systems, information, and culture with which today‟s leaders constantly wrestle.

Cross-cultural in nature, the program used face-to face (f2f) communication and

Information Communication Technologies (ICTs). Garnering resources and using wisdom to

cross multiple boundaries—geographical, interdisciplinary, and intercultural—successful

educational models often employ ICTs to reach and sustain leaders as learners who in turn

sustain their societal and corporate structures. The use of these ICTs in this institution allowed

educators to not “just do education as normal,” but to diffuse education throughout even remote

areas of society as it brought professors and learners together across geographic, national, and

intercultural boundaries. It also required an understanding of distance learning pedagogical

frameworks, such as that of Bocarnea, Grooms, and Reid-Martinez (2006). In many ways, this

blended-learning approach transcended the customary face-to-face environment that requires

participants to limit their dialog and interaction to specified learning periods in any given week.

Employing multiple delivery modes, this blended learning program incorporated two

course modules per term, with six terms throughout the length of the program. Each module

consisted of a one-week onsite residency in Sao Paulo, Brazil with intensive f2f instruction

followed by six weeks of online learning in a virtual classroom using ICTs. While the content of

each course rested on theoretical principles, each course required practical leadership

application.

Participants

Although this program consisted of 11 professors (7 males, 4 females) from a university

in the southeastern US, the study focused on the two lead professors (2 females) and the 17 Latin

American learners from multiple professions (7 males, 10 females). Learners chose this program

to enhance their leadership skills by pursuing a master‟s degree with a concentration in

educational leadership. Upon entry into the program, the age range of the learners was 23 to 53

with a mean age of 34. All except two learners completed the program and all forms of data

collection. The two who discontinued their studies (1 male, 1 female) terminated at the

conclusion of the second term for personal reasons.

Instrumentation and Data Collection

In order to understand this group, the researchers used multiple data collection strategies

to assess personal leadership development as it related to their respective roles within their

organizations throughout the two-year program and two years post-graduation. While so much

measurement over a four-year period has the potential of “tool fratricide,” multiple instruments

were used because of the intercultural and international dimensions of the program. Stark

language and cultural differences were presumed to require more attention to the nuance of

change within the learners. Constant and diligent oversight of the progress of the students in

understanding leadership in a global context was achieved through “erring” on the side of overmeasurement.

Self-assessments were administered at strategic points throughout the program—first and

second terms, midway, and end of program— not only providing insight into where the learners

began in this leadership journey, but also revealing their growth and development throughout the

program. Providing a psychological and leadership profile, these metacognitive activities

facilitated formative opportunities for learners to specifically explore their personal psychosocial

and cultural dimensions, leadership traits and styles, and conflict resolution preferences. Learner

communication preferences were also examined in light of the program‟s mentoring functions

and how communication supported conflict resolution.

First, psychosocial and cultural dimensions of the learners were probed. The psychosocial

dimension included self-assessments of learners‟ motivational levels, functional gifts, and

personality tendencies (Selig & Arroyo, 1989) as well as the 93-item Myers-Briggs Type

Indicator, Form M. In addition, two underlying cultural issues were continually monitored:

ethnocentrism and high/low context. Cultural acuity was first measured through a modified 18-

item ethnocentrism scale based on the work of Neuliep, Chaudoir, and McCroskey (2001), and

second by a 9-item high (collective) and low (individual) context scale developed from DeVito‟s

(2004) work, which was based on the research of Hall (1983), Hall and Hall (1987), Gudykunst

(1991), and Victor (1992). Due to the cultural differences in learners and the two lead professors,

both groups self-assessed in these areas.

Second, learners explored their various leadership traits and styles using Northouse‟s

(2004) 10-item Leadership Trait Questionnaire and 20-item Style Questionnaire. While

highlighting the leader‟s strengths and weaknesses, the Trait Questionnaire “quantifies the

perceptions of the individual leader and [five] selected observers” (p. 30). The Style

Questionnaire provided the opportunity for learners to self-assess their tendency toward task or

relationship behavior. To complement these quantitative measures, learners also reflected on

their leadership through time logs, personal leadership autobiographies, personal leadership

philosophies, and culminating portfolios.

Third, the learners‟ conflict resolution preferences were explored using Shockley Zalabak’s (2002) Personal Profile of Conflict Predispositions, Strategies, and Tactics. This 44-

item instrument measures preferred style for handling conflict: avoidance, competition,

compromise, accommodation, and collaboration.

And fourth, communication preferences were assessed with McCroskey and Richmond’s

(1996) Willingness to Communicate Scale (WTC) and Grooms and Bocarnea’s (2003) Computer Mediated Interaction Scale (CMIS). The WTC is a 20-item instrument that measures an

individual’s predisposition to communicate in a variety of contexts. Based on Grooms‟ (2000)

work on computer-mediated interaction, the CMIS is a 122-item instrument that measures the

importance of task and social learner-faculty and learner-peer interaction.

After compiling a personal psychological and leadership profile, learners conducted

organizational assessments to clarify their leadership roles, which helped them develop strategic

organizational goals. This process included planning, scheduling, implementing, and evaluating

organizational growth and aligning personal leadership goals within that context. All of these

activities were facilitated through the curriculum, which culminated in participants‟ professional

portfolios.

An additional instrument appraised mentoring the learners received during their program.

Based upon Jacobi‟s (1991) work, the following mentoring functions were explored on a 15-item

assessment: (a) acceptance/support/encouragement, (b) advice/guidance, (c) access to resources,

(d) challenge, (e) clarification of values and goals, (f) coaching, (g) information, (h) protection,

(i) role modeling, (j) social status, (k) socialization, (l) sponsorship, (m) stimulation of

acquisition of knowledge, (n) training/instruction, and (o) visibility/exposure.

To assess program quality in sustaining leadership development, the researchers

conducted formative program assessments using surveys, multiple onsite interviews, and onsite

focus groups to enable necessary adjustments to meet learner needs as they surfaced. The study

also used summative assessments such as graduation rate, cumulative grade point average

(GPA), and learner self-assessment of their leadership growth. Two years post-graduation, the

researchers solicited open-ended responses via email to determine where the graduates were in

terms of their careers and ongoing leadership development, also asking what impact the program

had on their current leadership placement.

Findings and Interpretations

Following analysis, findings and interpretations were divided into four major categories:

Leadership Development Program Outcomes, Strategically Designed Curriculum for Leadership

Development, Mentoring, and ICT/Blended Communication.

Leadership Development Program Outcomes

In examining program quality for sustaining leadership development, two levels of

summative outcomes were measured: one immediate and the other longitudinal. The first level of

outcome measurement was at the conclusion of the two-year program. This included graduation

rate, cumulative grade point average (GPA), and a qualitative component of leadership growth

self-analysis. Eighty-eight percent of the cross-cultural learners graduated (n = 15). Based on a 4-

point scale, the mean GPA was 3.8. Self-analysis comments reflected that 100% of the learners

experienced significant leadership growth at program completion. For example, one learner

noted, “Before I started this [program], I would look at my natural skills and find it hard to detect

the profile of a leader. Nevertheless, today I have a different view.” A second student expressed,

“My conclusion is that I have been transformed through the knowledge and wisdom acquired

during this master’s.” Finally, another said, “I have learned so much about myself and my

leadership style, traits, and abilities, and that has helped me to improve my performance . . . in

every situation I am expected to exert leadership.”

The second level of summative outcome measurement followed learners two years postgraduation. These longitudinal outcomes fell into two categories: career development and

continued self-assessed leadership growth. Aligning with the goals of the program, all learners

cited increased and sustained capacity for leadership in terms of their career development. Four

were pursuing additional graduate studies at institutions such as Harvard and the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology; two had moved to East Asia to assume educational leadership

responsibilities; and two were serving on executive educational boards. One, an entrepreneur in

the field of security, reported expanded growth and capacity in his organization. A second

entrepreneur began an English language program for adults and children. One, a banking vicepresident, credited the program with his ability to better understand human resources and for

increasing his team‟s capacity, which in turn increased quarterly earnings. Others also continued

to excel in their endeavors as a marketing research director, a teacher, a translator, and an export

analyst in a major medical supply company.

In addition to career development, learners reported continued leadership growth. Some

claimed that due to the learning and application of the knowledge gained from the program, they

were placed into higher levels of national and international leadership. All credited the program

with challenging and giving them space to develop their own leadership philosophies, resulting

in attitudinal and behavioral changes still demonstrated two years post-graduation. As

represented by the following response, learners provided powerful self-reports about their

changes: “the leadership training . . . gave me more knowledge of peoples‟ behavior and polished

my soul and heart . . . It brought me wisdom and experience which I can apply in the

relationships of everyday life and work.” Others concurred, reporting that the most important

leadership moral and ethical principles they learned were how to deal with and influence people.

This influence included their ability to more effectively handle issues of social justice by

implementing appropriate policies, processes, and procedures that assured equity within their

organizations and teams. In turn, this increased the human resource capacity within their

leadership span. According to the participants, such attitudes and behaviors sustained their

leadership and helped them grow other leaders.

Strategically Designed Curriculum for Leadership Development

Catapulting the success of these outcomes was a curriculum strategically designed around

three areas: (a) course content, (b) personal self-assessments, and (c) organizational assessments.

Interviews with students two years post-graduation resulted in an interesting finding best

expressed by one student representing the group: “I can say that the curriculum is still alive

within me and I really perceive myself as living, walking curriculum.” This reflects that the

curriculum lives within learners as they now employ and teach concepts gained in the program

either directly or indirectly. They see themselves as living curricula as they constantly evolve

and continue to grow as leaders. As another student stated, “I do believe it is still living within

me—especially about leadership.”

Course content. Guided by professors, the first dimension of the curriculum provided

materials and experiences essential for leadership. The course content included effective

leadership theories and models; philosophical and ethical/moral moorings in leadership; effective

communication, conflict resolution, and negotiation theory and skills; organizational strategic

planning, finances, start-up, and operations; and specific school applications, such as curriculum

methods and assessments. Learners also studied research design and developed a culminating

professional project while completing multiple strategically structured exercises incorporating

worldview, values, and ethics. The program and curriculum were consistently monitored and

assessed on a quarterly basis, ensuring continual alignment with immediate and projected

longitudinal learner needs in the cross-cultural context.

Personal self-assessments. To understand their psychological and leadership orientation,

learners‟ used multiple measures. Assessment occurred in three categories: (a) psychosocial and

cultural dimensions, (b) leadership traits and styles, and (c) conflict resolution preferences.

Psychosocial and cultural dimensions. Using assessments from Selig and Arroyo

(1989), learners demonstrated capacity for self-appraisal while recognizing the diversity of gifts,

motivational levels, and personality tendencies of others. Equipped with this knowledge, they

learned to use encouragement and positive reinforcement to empower their teams. For

themselves and those around them, they demanded a high ethical and moral standard.

Based on the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, almost 75% (n = 11) of the learners had

judging style personalities, which indicated a preference for structured and decisive

environments. Forty percent (n = 6) were sensing, thinking, and judging (STJ). Thorough,

dependable, logical, practical, and realistic are characteristics representative of the STJ

personality, which values “security, stability, belonging, preserving traditions, and applying

established skills” (Clancy, 1997, p. 434). Analytical and concrete with a keen sense of

responsibility, these learners work steadily toward goals while their desire for routine and order

match their linear-thinking style. They carried out their responsibilities consistently and

forcefully (The Myers & Briggs Foundation, n.d.). There was an almost even distribution

between those preferring Introversion and those preferring Extraversion (one additional

extravert), and the remainder of the learners represented a range of the Myers-Briggs

psychological types.

The Generalized Ethnocentrism Scale reflected that all 15 Latin American learners and

the two lead U.S. professors and mentors had low ethnocentrism scores. In response to the highand low-context scale derived from DeVito (2004), all 15 Latin American learners had high

high-context scores, aligning with the expected cultural norms. This reflects a need for facesaving and conflict avoidance, yet also that relationship is of utmost importance. Follow-up

focus group responses demonstrated the same theme. In contrast, the two lead U.S. professors

scored high in low-context, which revealed their individualistic natures and attendant explicit

and direct communication.

Leadership traits and styles. From their Leadership Trait Questionnaire selfassessments, this group primarily described themselves as trustworthy, determined, perceptive,

and persistent. The Style Questionnaire revealed that 40% (n = 6) of the group reported a balance

in their relationship versus task leadership orientation. Three were task-oriented, one of which

was extremely task-oriented. These were of particular interest because at the end of the program,

all three reported dramatic leadership changes. One credited the program with significant

improvement in his people skills, while another noted he now appreciated people more. The

learner who identified as extremely task-oriented said, “For the first time in years, I am paying

more attention to people . . . than to tasks and results . . . this [program] time was a turning point

in my life.”

Self-reflection through learners‟ autobiographies, philosophies, time log analyses, and

portfolios demonstrated that this program enhanced leadership capacity. These exercises required

learners to increase their self-awareness, resulting in what they referred to as personal

transformation. Each learner reported that this transformational process helped them prioritize

and focus while gaining strength to overcome obstacles and achieve leadership vision and goals.

Leadership trait and style transformation, a recurring theme, occurred through and throughout

this educational process.

Conflict resolution preferences. Important to leaders is the ability to manage conflict

(Hackman & Johnson, 2004; Shockley-Zalabak, 2002). From the learners‟ results on the

Shockley-Zalabak (2002) Conflict Profile, this group preferred a collaborative style of conflict

resolution, with males preferring a competitive style more often than females. Compromise was

the second most popular choice, and one learner chose accommodation. Of interest, when

responding to the WTC scale, this group confirmed their need for relationship: almost 75% of the

cohort was willing to communicate, with 40% highly willing. This may explain why this group

was primarily collaborative in their conflict resolution style.

In summary, these learners were well-balanced, self-reflective individuals. They were

predominately relationship rather than task-oriented and were willing to collaboratively resolve

conflict. Their ability to incorporate program information, self-reflection, and lived experience

enabled learners to transform themselves and their leadership capacity. By placing these

psychosocial, cultural, leadership, and conflict resolution assessments at strategic points

throughout the program, the curriculum modeled the need for ongoing self-transformation

through sustained self-learning.

Organizational assessments. Learners assessed their organizations by directly applying

knowledge gained from course content. Organizational assessments enabled learners to

determine direction for their leadership, while Gannt charts and other planning tools helped them

anticipate and define strategic goals for organizational growth.

As the above assessments suggest, learners gained substantial self-knowledge during this

program. In tandem with the organizational assessments and strategic organizational goal

development, learners evaluated their personal leadership growth and adjusted it in light of

organizational needs, assuring alignment. In evaluating themselves, learners eagerly applied

what they discovered; however, challenges, including the angst of personal reflection, assailed

the learners on many fronts. As one student described it, “I can say that the whole program was

like a „watershed‟ for me.” Throughout the process as learners discovered their strengths and

weaknesses, professors mentored them in not only developing a strategic plan for personal

growth, but also in refining their leadership at each stage of development.

Mentoring

Embedded throughout the program, Grooms and Reid-Martinez‟s (2006, 2008)

interaction function and Jacobi‟s (1991) mentoring function surfaced repeatedly. Supporting

Grooms‟ (2000) work, the CMIS responses revealed learners desired task interaction in three

categories: (a) informational feedback, (b) evaluative feedback, and (c) intellectual discussion.

Regarding informational feedback and mentoring functions, all learners stated that access to

resources and information about organizational culture and key personnel were frequently to

always provided. In addition, all reported that professors frequently to always clarified goals and

values through evaluative feedback and mentoring. While all noted knowledge acquisition

occurred through intellectual discussions, one learner asked for more challenges in those

discussions. This illustrates that task interaction directly related to the mentoring functions.

Additional CMIS findings support that socio-emotional functions of mentoring and

interaction in the leadership development process fell into two categories: (a) motivation/support

and (b) socializing, again aligning with the work of Grooms (2000). In the area of

motivation/support and its related mentoring functions, all learners indicated they frequently to

always received: adaptation of instructional materials; acceptance, support, and encouragement;

advice and guidance; coaching; role modeling; and a safe and supportive environment in which

to learn. For mentoring functions that paralleled socializing, learners had varied responses. Fiftyseven percent agreed that professors frequently to always enhanced their social status. Fifty

percent said they frequently to always received visibility and exposure, while 64% said they

received sponsorship or advocacy. Only 7% (n=1) said they were socialized into their

professions, perhaps indicative of the variety of professions represented and the transcontinental

dimensions of the program with professors and students in different cultures and geographical

locations. Thus, all 15 mentoring functions occurred at various levels with mentoring sustained

throughout the program.

ICT/Blended Communication

Designed to meet the needs of current and future leaders and to provide learning from a

cross-cultural perspective, one distinctive element of this program was the virtual, blended

learning environment. This context, which demanded the use of ICTs and f2f platforms, required

learners to operate in today‟s technology-laden global environment while maintaining the

richness of interpersonal communication. As was expected, learners and professors used the f2f

environment to establish and deepen relationships. It also afforded the opportunity and format for

quickly resolving issues as they sat together in one location. At the same time, the virtual

environment allowed learners to connect with greater breadth of information and with the

broader community of experts while remaining in touch with their professors after the f2f

meetings. By combining the richness of f2f and the connectivity of ICTs, learners sustained

communication over time and space.

Through assignment assessments, observations, and interviews, the professors observed

student use of ICTs in the learning process. Although the program was designed with designated

roles for technology, learners quickly adapted ICTs to meet their cultural expectations and needs.

For example, in online assignments created to teach problem solving, these learners

automatically moved to a blend of f2f and virtual communication. Requiring sensitivity and

adjustment in working with learners on technological adaptations, professors modeled

empowerment, an important leadership skill. Additionally, the process taught learners

advantages and disadvantages of various communication channels.

Through ICT connectivity, professors gave the cross-cultural learners guidance; as a

team, they provided responses to learners on an almost 24/7 basis. As technology allowed

learners to interact continuously with peers, it also facilitated swift and easy connections with

local, regional, national, and international experts. This experience further prepared learners to

incorporate ICTs at new levels of organizational team building as they came to understand which

medium applied most appropriately to which messages and functions of communication and

leadership. For example, learners were encouraged to network for virtual mentoring and to use

ICTs for the content of their courses (e.g., virtual libraries, audio and video streaming, chat

rooms, and the early stages of Web2 technologies). Furthermore, they gained an understanding

of how to lead in cross-cultural, virtual contexts as they immediately applied this new leadership

knowledge in their organizations. This presented yet another avenue for assuring the ease of

sustaining learners‟ leadership through sustained learning, sustained support of a network of

peers, and sustained and deepened organizational relationships as they learned to use ICTs as an

important means of communication for broader networking and knowledge development.

Discussion

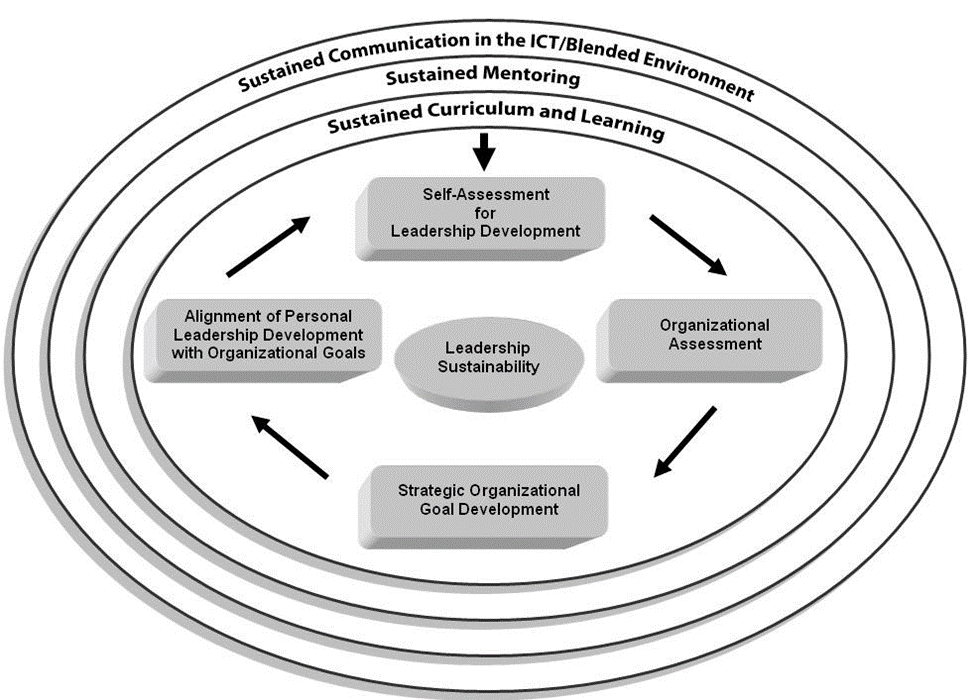

From this case study, an educational model emerged illustrating the synergistic

relationship that facilitates sustained leadership in educational programs. Key elements

confirmed that leadership sustainability, demonstrated through learner outcomes, was an intricate

weaving of multiple factors in the educational program. Three critical areas emerged: (a)

sustained communication in the ICT/Blended environment, (b) sustained mentoring, and (c)

sustained curriculum and learning. Figure 1 portrays the elements and relationships of

sustainable leadership development model.

Sustained Communication in the ICT/Blended Environment

The first key element, sustained communication, resulted from the blended learning

environment that combined f2f and ICTs, including the use of virtual classrooms, so that learners

were connected with information, peers, professors, and experts. Due to the cross-cultural, crosscontinental dimensions of this educational endeavor, use of ICTs made a dynamic 24/7 learning

opportunity possible. It also facilitated timely post-graduation leadership development follow-up.

Additionally, in this case study learners used media for their own purposes and in their

own ways, and the professors adapted to that usage. This was congruent with traditional

understanding of media uses-and-gratifications and functions of such media, such as

transmission of information and culture (e.g., Carey, 1989; Katz, Blumler, & Gurevitch, 1974;

Katz, Haas, & Gurevitch, 1973; McQuail, Blumler, & Brown, 1972).

In the communication process, students were empowered to more clearly manifest their

leadership roles in both the f2f and virtual environments as they transmitted a new cultural ethos

grounded in their axiological, ontological, and epistemological development. This development,

especially the learner‟s self-analysis with its transformational dimensions, revealed the strategic

and essential roles of both the educational medium and the learner‟s newly enhanced ontological

and axiological leadership character and fiber. This character was the important membrane

through which learners‟ virtual communities evolved as they were created and sustained through

the transmission of culture using multiple mediated channels. With the merger of medium and

culture, the old adage that “the medium is the message” (McLuhan, 1964) surfaced as media

influenced the ways in which these learners defined their newly created virtual communities with

their related leadership and learning development.

Most importantly, the creation of these communities deepened learners‟ leadership

capabilities. The connectivity offered by technology aided in sustaining the participants‟

leadership in healthier and more intentional ways. Taking advantage of the strengths of available

media, learners came to understand best leadership communication practices. This sustained

communication in the ICT/Blended environment promoted leadership sustainability over time

along with leadership succession as the learners trained future leaders.

Sustained Mentoring

Sustained mentoring surfaced as an essential element in this leadership development

program, confirming Stoddard‟s (2003) conclusion that “in a real sense, mentoring is

leadership—leading a mentoring partner to self-discovery, self-fulfillment, and paradoxically,

selflessness” (pp. 192-193). Wilkes (1998) further stated that mentoring is how leaders “prepare

the next generation of leaders for service [and] unless there are future leaders, there is no future”

(p. 236). Indeed as individuals in this study were observed two years post-graduation, all were

actively teaching, modeling, or implementing, as well as mentoring, what they had been taught.

These learners understood mentors to be professors who were guides and facilitators

providing content, pointing the way, assessing for quality, and filling in gaps with

recommendations, information, and wisdom as needed. To further assure that mentoring took

place, the curriculum was embedded with assessments related to Jacobi‟s (1991) mentoring

functions and was designed to operate in tandem with the professors mentoring in the f2f and

ICT learning environments. These assessments allowed timely and quality feedback to learners

throughout the process. As a team, professors provided 24/7 mentoring support through

interpersonal and mediated communication. When combined with the embedded mentoring

functions, this created a fail-safe opportunity to ensure sustained mentoring.

Sustained Curriculum and Learning

Designed to provide transformational opportunities for learners, the curriculum also

created a sustained learning environment. As mentioned earlier, learners demonstrated this by

noting that the curriculum “still lives within them,” indicating the sustained curriculum had a

dynamic rather than a static effect.

The curriculum’s transformational element resulted from the synergy of leadership

theory, self-analysis, and praxis. Most importantly, these three were placed within ethical and

practical applications that pushed the learners to understand themselves in real-life contexts. The

learners had to first “know themselves” and their ethics and values to better assess their

organizational leadership. This ontological and axiological perspective required learners to

complete a number of leadership self-assessments that were revisited and reassessed at different

points of the program. This process demonstrated levels of personal internal transformation.

When combined with their organizational assessment, learners checked for alignment and made

appropriate changes in their personal leadership development in light of strategic organizational

goals. By helping learners continuously make connections and alignments between their deep

internal locus of control with leadership and their external leadership environment, the learners

as leaders were better positioned to effectively influence and meet the needs of their evolving

organizations. This resulted in sustainable leadership through sustained curriculum and learning

that granted a high level of satisfaction for these learners as they transformed themselves and

their organizations.

The Model and Sustainable Leadership Education Programs

Mirroring contemporary learning theories and consistent with the earlier works of ReidMartinez (2006) and Reid-Martinez, Grooms, and Bocarnea (2009), the Sustainable Leadership

Development Model demonstrates the importance of educational programs combining social

Grooms & Reid-Martinez / INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEADERSHIP STUDIES 425

International Journal of Leadership Studies, Vol. 6 Iss. 3, 2011

© 2011 School of Global Leadership &Entrepreneurship, Regent University

ISSN 1554-3145

constructivism (Berger & Luckman, 1967; Vygotsky, 1978) and connectivism (Siemans, 2005)

for successful learning. This approach recognizes that students do not learn strictly within the

confines of their educational institutions, but rather within the broader context of their personal

lives. In this educational program, use of ICTs expanded the learner‟s ability to gather

knowledge from multiple contexts.

Consequently, the boundaries of the educational institution blurred as ICTs and the larger

community were integrated into the learning process. With ICTs and their capacity to transmit

both information and culture, learners worked collaboratively to bring their own and others‟

worldviews and experiences into the learning community. In this process, they negotiated and

generated meaning through shared understanding and experiences filtered by their axiological

screens. Thus, in this constructivist environment education moved from a single individual‟s

solitary pursuit of knowledge to a collaborative learning community that reciprocally shaped and

informed learners as they in turn shaped and informed the community. Such an approach focused

on constant regeneration, refinement of personal internal values, and transformation of the

leaders within their learning communities, supporting the earlier work of Hargreaves and Fink

(2003, 2004, 2006) that implied the leader as learner is key to sustainable leadership.

Simultaneously, a connectivist approach to learning was observed as well. Technology

created a dynamic nature of multiple networks, and leaders as learners sifted through rapidly

changing databases. They gleaned and gathered from the montage of regional and global experts,

journeying through constantly evolving social networks and congregating electronically with

others to discuss themes and ideas. In these shifting and fluid digital communities, learners used

a constructivist approach filtered through their ontology and axiology to garner what they needed

for leadership empowerment and sustainability. As they married their internal constructivist state

with their external connectivist environment, the learners developed knowledge in the social

construction and practice of their leadership. This ongoing connective and constructive process

of learning and leading helped to create sustainable leaders.

Limitations and Future Research

Limitations of the current study center on the question of over-measurement. As noted

earlier, over-measurement can create a problem with “tool fratricide,” which may have skewed

the results in this leadership development study. Future researchers should select instruments that

would be most effective for studying nuances of leadership development in specific intercultural

and international learning environments. Future research could also focus on which learning

methods and andragogies are best aligned within the cultures of both the learners and the

facilitators. At the same time, research could focus on third culture development as it relates to

leadership education. Third culture here references what occurs in the new learning spaces

created through contemporary use of virtual and f2f blended education to create and sustain

leadership development in global learning initiatives.

Conclusion

In conclusion and in response to the research question, this study suggests that a strong

leadership program will model the way of empowerment and development of individuals rather

than deplete human resources as it encourages sustained leadership through sustained

communities of learning. This educational initiative immersed learners in a virtual/blended

learning environment that focused on personal transformation in order to transform their

organizations and communities.

Through modeling and mentoring, learners were provided with intentional leadership

support structures and, for their futures, they gained the ability to build sustained learning

communities for sustained leadership within themselves and their followers. Such sustained

learning creates a cycle of ongoing leadership development that continuously moves current and

future leaders from information to the creation of reservoirs of knowledge and wisdom, further

deepening and sustaining leadership. This continuous leadership growth provides an important

constant in the evolution of sustainability, demonstrating that like sustainable development,

sustainable leadership represents a process, not an end state.

References

Bennis, W. (1998). Becoming a leader of leaders. In R. Gibson (Ed.), Rethinking the future (pp. 148-163). London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Berger, P. L., & Luckman, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Bocarnea, M. C., Grooms, L. D., & Reid-Martinez, K. (2006). Technological and pedagogical considerations in online learning. In A. Schorr & S. Seltmann (Eds.), Changing media markets in Europe and abroad: New ways of handling information and entertainment content (pp. 379-392). NY/Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

Brady, A. K. O. (2005). The sustainability effect: Rethinking corporate reputation in the 21st century. NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brandon, P. S., & Lombardi, P. (2005). Evaluating sustainable development in the built environment. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. NY: Routledge. Clancy, S. G. (1997). STJs and change: Resistance, reaction, or misunderstanding? In C. Fitzgerald & L. K. Kirby(Eds.), Developing leaders: Research and applications in psychological type and leadership development (pp. 415-438). Palo Alto, CA: DaviesBlack Publishing.

DeVito, J. A. (2004). The interpersonal communication book (10th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Drucker, P. F. (1996). Forward. In F. Hesselbein, M. Goldsmith, & R. Beckhard (Eds.), The leader of the future (pp. xi-xv). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Fullan, M. (2005). Leadership & sustainability: Systems thinkers in action. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

Grooms, L. D. (2000). Interaction in the computer-mediated adult distance learning environment: Leadership development through online education. Dissertation Abstracts International, 61(12),4692A.

Grooms, L. D., & Bocarnea, M. C. (2003). Computer-mediated interaction scale. Unpublished manuscript, Regent University, Virginia Beach, VA.

Grooms, L. D., & Reid-Martinez, K. (2006, November). Crossroads: The intersection of mentoring, culture, and learning environment in contemporary leadership education. Presentation at the annual International Leadership Association Conference, Chicago, IL.

Grooms, L. D., & Reid-Martinez, K. (2008, March). Creating and sustaining cross-cultural leaders through personal interaction and mentoring. Presentation at the Women as Global Leaders Conference, Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Gudykunst, W. B. (1991). Bridging differences: Effective intergroup communication. Newbury Park: Sage.

Hackman, M. Z., & Johnson, C. E. (2004). Leadership: A communication perspective (4th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Hall, E. T. (1983). The dance of life: The other dimension of time. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, M. R. (1987). Hidden differences: Doing business with the Japanese. Garden City, NY: Anchor Press.

Hargreaves, A. (2007). Sustainable leadership and development in education: Creating the future, conserving the past. European Journal of Education, 42(2), 223-233.

Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2003). The seven principles of sustainable leadership. Retrieved from http://www2.bc.edu/~hargrean/docs/seven_principles.pdf

Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2004). The seven principles of sustainable leadership [Electronic version]. Educational Leadership, 61(7), 8-13.

Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2006). Sustainable leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 6(4), 505-532.

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1974). Utilization of mass communication by the individual. In J. G. Blumler & E. Katz(Eds.). The uses of mass communications: Current perspectives on gratifications research (pp. 19-32). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Katz, E., Haas, H., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). On the use of the mass media for important things. American Sociological Review, 38(2), 164-181.

Ling, O. G. (2005). Sustainability and cities: Concept and assessment. Singapore: World Scientific.

McCroskey, J. C., & Richmond, V. P. (1996). Fundamentals of communication: An interpersonal perspective. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. NY: Signet Books.

McQuail, D., Blumler, J. G., & Brown, J. R. (1972). The television audience: A revised perspective. In D. McQuail(Ed.), Sociology of mass communications (pp. 135-165). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin.

Nanus, B. (1992). Visionary leadership: Creating a compelling sense of direction for your organization. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Neuliep, J. W., Chaudoir, M., & McCroskey, J. C. (2001). A cross-cultural comparison of ethnocentrism among Japanese and United States college students. Communication Research Reports, 18, 137-146.

Northouse, P. G. (2004) Leadership: Theory and practice (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Portney, K. E. (2003). Taking sustainable cities seriously: Economic development, the environment, and quality of life in American cities. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Reid-Martinez, K. (2006). What’s that in your hand: Leadership and collaborative learning in the 21st century. Paper presented at the COG International Conference of Educators, Indianapolis, IN.

Reid-Martinez, K., Grooms, L. D., & Bocarnea, M. C. (2009). Constructivism in online distance education. In Encyclopedia of information science and technology, Vol. 2 (2nd ed., pp. 701-707). Hershey, PA: Idea Group.

Riddell, R. (2004). Sustainable urban planning: Tipping the balance. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Selig, W. G., & Arroyo, A. A. (1989). Loving our differences. Virginia Beach, VA: CBN Publishing.

Shockley-Zalabak, P. (2002). Fundamentals of organizational communication: Knowledge, sensitivity, skills, values (5th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Siemans, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of

Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1). Retrieved from http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Sorensen, A., Marcotullio, P. J., & Grant, J. (2004). Towards sustainable cities. In Towards sustainable cities: East Asia, North American, and European perspectives on managing urban regions (pp. 3-23). Urlington, VT: Ashgate.

Stoddard, D. A. (2003). The heart of mentoring: Ten proven principles for developing people to their fullest potential. Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

Sustainability Leadership Institute (n.d.). What is sustainability? Retrieved from http://www.sustainabilityleaders.org/whatis/

The Myers & Briggs Foundation (n.d.). MBTI basics. Retrieved from http://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Sustainable Development. (1992). Agenda 21. Core publications. Retrieved from

http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/english/agenda21toc.htm

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 42/187 (1987). Report of the world commission on environment and development. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/42/ares42-187.htm

Victor, D. A. (1992). Interpersonal business communication. NY: Harper Collins.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilkes, C. G. (1998). Jesus on leadership: Discovering the secrets of servant leadership.

Wheaton, IL: Tyndale House Publishers.

About the Authors

Linda D. Grooms, Ph.D., currently serves as an associate professor of educational leadership and most

recently served as the program director for the Latin American Project in the School of Education at

Regent University. With almost three decades of leadership experience and degrees in both

educational and organizational leadership, she has a passion for nation building through the

transformational leadership of educational systems. Dr. Grooms conducts leadership training both

nationally and internationally in such places as Stuttgart, Germany; Lima, Peru; and Sao Paulo, Brazil.

In addition, she has presented at such organizations as the European Communication Congress,

European Communication Research and Education Association, National Communication

Association, International Communication Association, International Leadership Association, Society

for Information Technology and Teacher Education, and the Sloan-C International Conference on

Asynchronous Learning Networks in such places as Rome, Munich, Hamburg, Calgary, Vancouver,

and Dubai. Her research interests include leader identity, authenticity, and spirituality;

transformational, sacrificial, and crisis leadership; adult, distance, and online learning and pedagogy;

interpersonal, computer-mediated, and organizational communication; personality or psychological

types; and critical thinking.

Email: lindgro@regent.edu

Kathaleen Reid-Martinez, Ph.D., currently serves as vice-president for academic affairs at MidAmerica Christian University. She also is the executive advisor to the Center for Effective

Organizations at Regent University and is senior advisor to the Partners for Peace Consortium on

virtual education for leaders. Since completing her degree in communication, she has spent the

last two decades in communication and leadership research as well as administration, teaching,

and consulting. Dr. Reid-Martinez has served as dean of a school of leadership studies and

presented at or consulted to such organizations as the European Communication Congress;

European Communication Research and Education Association; National Communication

Association; International Communication Association; International Leadership Association;

Department of Education in the Netherlands; the NATO Defense College in Rome, Italy; the

Federal Degree Granting Institute; the National Institute of Justice; Jones Cable, now owned by

Time Warner; and the Bureau of Education in the People’s Republic of China. Most recently, Dr.

Reid-Martinez has worked to develop health programs in the Middle East and undergraduate

programs in South Africa. Spanning five continents, she has pursued a better understanding of

leaders, their education, and their communication.

Email: kreid-martinez@macu.edu

About Regent

Founded in 1977, Regent University is America’s premier Christian university with more than 11,000 students studying on its 70-acre campus in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and online around the world. The university offers associate, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in more than 150 areas of study including business, communication and the arts, counseling, cybersecurity, divinity, education, government, law, leadership, nursing, healthcare, and psychology. Regent University is ranked the #1 Best Accredited Online College in the United States (Study.com, 2020), the #1 Safest College Campus in Virginia (YourLocalSecurity, 2021), and the #1 Best Online Bachelor’s Program in Virginia for 11 years in a row (U.S. News & World Report, 2023).

About the School of Business & Leadership

The School of Business & Leadership is a Gold Winner – Best Business School and Best MBA Program by Coastal Virginia Magazine. The school also has earned a top-five ranking by U.S. News & World Report for its online MBA and online graduate business (non-MBA) programs. The school offers both online and on-campus degrees including Master of Business Administration, M.S. in Accounting (Tax or Financial Reporting & Assurance), M.S. in Business Analytics, M.A. in Organizational Leadership, Ph.D. in Organizational Leadership, and Doctor of Strategic Leadership.