From the Individual to the World: How the Competing Values Framework Can Help Organizations Improve Global Strategic Performance

Scott Lincoln

Handong Global University

In a competitive global economy, organizations need to be able to redefine themselves and their strategic visions. However, many change initiatives are unsuccessful due to the lack of consideration for organizational cultural variables. The Competing Values Framework, when used in conjunction with strategic planning, can increase the chances of success. Tools like the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument and the Managerial Behavior Instrument provide concrete ways to assess where the organization is, where it should be, and realigning the organization from the individual manager to the entire organizational culture.

Confucius said in his tract known as The Great Learning that to build a great kingdom you must first tend to your own state; to build a great state, you must first tend to your own family; to build a great family, you must first cultivate yourself; and to cultivate yourself, you need to dedicate yourself to learning. This tract, written for aspiring leaders in the 5th century B.C., still holds true today. If we want our organization to become competitive on the global stage, we need to have the appropriate organizational culture to be able to execute the proper strategies. To affect this type of metamorphosis, we must first look to ourselves. Once we have developed ourselves, we may influence others around us, and thereby transform our organization. The Competing Values Framework (CVF) is an eminently practical tool to help analyze not only the individual but also the organizational culture, and to help plot a course for the organizational culture change that is a necessary part of any sweeping strategic initiatives.

The Competing Values Framework

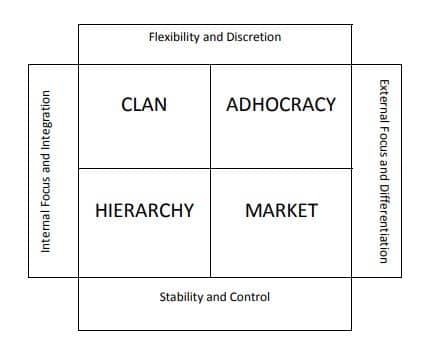

The CVF evolved out of research to determine the key factors of organizational effectiveness. This research initially yielded a comprehensive list of 39 possible indicators to measure effectiveness. Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983), through factor analysis, condensed this list into a more parsimonious set of two major dimensions, which defined four major quadrants representing opposite and competing assumptions (see Figure 1). The first dimension ranges from flexibility and discretion on one end, to stability and control on the other. The second dimension measures the degree to which the organization emphasizes internal focus and integration or external focus and differentiation (Cameron & Quinn, 2006). The four major quadrants defined by these two axes were originally labeled the Human Relations Model, the

Open System Model, the Internal Process Model, and the Rational Goal Model (Quinn & Rohrbaugh). These respective quadrants have alternatively been labeled as the group, developmental, hierarchical, and rational cultures (Denison & Spreitzer, 1991); collaborate, create, control, and compete (Cameron, Quinn, DeGraff, & Thakor, 2006); and also clan, adhocracy, hierarchy, and market cultures (Cameron & Quinn). In this study, I will opt for the latter nomenclature.

The clan culture is like an extended family. This type of organization emphasizes teamwork, employee involvement, empowerment, cohesion, participation, corporate commitment to employees, and self-managed work teams. It is held together by loyalty and tradition. In this context, leaders are thought of as mentors or parent figures. Their main responsibilities are to empower employees, and facilitate their participation, commitment, and loyalty (Cameron & Quinn, 2006).

The adhocracy culture is a dynamic, entrepreneurial, and creative organization. This organization thrives in an uncertain, ambiguous, and turbulent environment. The common values are innovation, flexibility, adaptability, risk taking, experimentation, and taking initiative. Leaders are also expected to be visionary, innovative, and risk oriented (Cameron & Quinn, 2006).

The hierarchy culture is a formalized and structured bureaucracy. This culture values efficiency, reliability, predictability, and standardization. Fast and smooth operations are maintained by strict adherence to the numerous rules, policies, and procedures. The employees throughout the multiple hierarchical levels have almost no discretion. Leaders in this organization are expected to be good organizers and coordinators, and minimize costs. The market culture is fiercely competitive and goal oriented. They focus on productivity, profitability, market share and penetration, and winning. Leaders in this culture are expected to be hard driving, tough, and demanding competitors (Cameron & Quinn, 2006). One culture is not necessarily better than the others. The proper culture for each organization depends on the organization’s industry and strategy. For example, Gregory, Harris, Armenakis, and Shook (2009) found a positive relationship between clan cultures and patient satisfaction in healthcare facilities. Some early research also indicated that in a university setting, clan cultures scored higher on student educational satisfaction, student personal development, faculty and administrator employment satisfaction, and organizational health (Cameron & Freeman, 1991). However, a different study found that organizational effectiveness in institutions of higher education was highest in organizations that emphasized both the adhocracy and hierarchy cultures (Cameron, 1986).

A tool known as the Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (or OCAI) is used to determine the organization’s dominant culture. The OCAI contains 6 to 24 items, each with four alternatives. The respondents rank each of the four alternatives using an ipsative rating scale, that is, they divide 100 points among the four alternatives. This leads to greater differentiation than using a Likert scale because it forces respondents to trade off between the alternatives, rather than allow them to rate each alternative highly (Cameron & Quinn, 2006).

Application to the Individual/Behavioral Complexity

Once the organization’s dominant culture has been established, then the individual manager needs to discover their own dominant leadership style. The most effective way to determine one’s own dominant leadership style is to use the Managerial Behavior Instrument (MBI), which has been shown to correlate to the quadrants of the CVF (Lawrence, Lenk, & Quinn, 2009). This instrument should be completed, not only by the manager in question, but also by the manager’s peers, subordinates, and supervisors. The data from the completed instruments are compiled into a single feedback report which indicates strengths and weaknesses in the manager’s ability to demonstrate leadership styles consistent with the four quadrants of the CVF. Cameron and Quinn (2006) have found that the most effective managers—those rated as most successful by their subordinates, peers, and superiors and those who tend to rise quickly in the organization—demonstrate a leadership style that matches that of their organization’s dominant culture. However, it seems that this is a minimal measure of effectiveness, rather than an ideal.

There is a growing body of research which supports the idea that the best managers are those that can display all four managerial styles in turn, contingent on the current situation. This is known as behavioral complexity. Numerous studies confirm that leaders who can balance competing roles are evaluated more highly for their effectiveness and for other performance measures (Bullis, Boal, & Phillips, 1992; Denison, Hooijberg, & Quinn, 1995; Hart & Quinn, 1993; Hooijberg, 1996) while still maintaining a measure of behavioral integrity and credibility (Cameron et al., 2006; Denison et al., 1995). Tsui (1984) supported the idea that leaders with behavioral complexity are better able to meet multiple and competing demands of the organization, and Weick (2003) also found that these leaders have greater adaptability. Recent research also shows that behavioral complexity has a significant effect on performance of selfmanaged teams (Zafft, Adams, & Matkin, 2009). Therefore, it is obviously beneficial to the organization to have managers high in behavioral complexity. Lawrence et al. (2009) developed the CVF Managerial Behavior Instrument to measure behavioral complexity and predict managerial effectiveness. The need for managers who can balance leadership behaviors is especially important during periods of organizational transition (Belasen & Frank, 2008).

Leading Strategic and Cultural Change

“The 21st century may very well become known as the century of the global world” (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004, p. 3). Globalization is making business more complex, and professionally demanding. There is an increase in risk and uncertainty caused by the virtual disappearance of boundaries between countries and regions on the global competitive map (Kluyver & Pearce, 2006). The strategies that worked in the past are no longer guaranteed to produce satisfactory results. Organizations need to adapt to the changing conditions globalization has created. Change is inevitable; the only uncertainty is whether this change will be random or planned. Leaders need to be change agents. Leading change is extremely challenging and risky. Many companies have tried to implement change strategies, such as TQM initiatives, downsizing, and reengineering. However, according to various surveys, only 20% of companies achieve success with quality objectives, nearly 75% were found to be worse off in the long term after downsizing, and 85% of firms reported little or no gain from reengineering efforts (Cameron & Quinn, 2006). Many of these failures were likely caused by a failure to adequately align the organizational culture with the change effort. Schein (1985) noted that a culture which is rooted in deeply held, underlying assumptions and strategies that are incompatible with these assumptions will be resisted. Kluyver and Pearce (2006) recognized that organizational culture can inhibit or defeat a change effort. Cameron and Quinn argued that organizational culture change must occur before other initiatives can be successful. Therefore, leadership teams need to plan for organizational culture change in tandem with any major strategic realignment. The CVF is well suited for this task and fits naturally with strategic planning because, when used in culture change sessions, it gives the participants a model through which they can express their need for change, while at the same time discover why they themselves may be resistant to the very change they are planning (Hooijberg & Petrock, 1993).

Hughes and Beatty (2005) described strategy as a learning process that includes five elements: (a) assessing where you are, (b) understanding who you are and where you want to go, (c) learning how to get there, (d) making the journey, and (e) checking your progress. Cameron and Quinn (2006) listed six steps for initiating organizational culture change. These six steps are: (a) reaching consensus on the current culture, (b) reaching consensus on the desired future culture, (c) determining what the changes will and will not mean, (d) identifying illustrative stories, (e) developing a strategic action plan, and (f) developing an implementation plan. Clearly, a big part of the strategic steps of assessing where you are and understanding who you are should include determining the current culture by completing an OCAI. The OCAI includes two columns: one for the current culture, and one for the preferred culture. This allows the participants to clarify what cultural aspects they think should be changed going into the future. Reaching a consensus on this desired future culture is an integral part of the strategic step of deciding where you want to go. This idea of reaching a consensus is critical to get everyone on the same page. Lack of teamwork is one of the main reasons strategic leadership teams fail even though they contain many talented individuals (Hughes & Beatty). The next step in the CVF is to determine what the changes will and will not mean. This means to clarify in specific terms what the new culture should look like, and what pitfalls should be avoided. After that, illustrative stories should be presented that represent the new values that the organization hopes to achieve. Once these types of stories become widespread throughout the organization, they can introduce a strategic shift (Boje, 1991). The following steps of developing a strategic action plan and implementation plan are to nail down exactly what steps are necessary to change the culture from what it is today to what we want it to be in the timing of each of the steps. It is also important that structure, systems, processes, and people are considered to make sure that each is in alignment with the change initiative (Kluyver & Pearce, 2006). These final four steps of the CVF can be included in the strategic step of learning how to get there. The final steps in the strategic process are to make the journey, and check your progress. Simply put, these mean implementing your plans while continuously monitoring that all the changes are on track.

Conclusion

Globalization has changed the nature of the game for many organizations. These organizations need to consider making sweeping changes in their strategy. However, organizational culture may serve as a barrier. A strong organizational culture can be a great asset by helping to align everyone in the organization in the same direction. However, when the direction needs to be changed, management can find itself swimming against the current. Since many change initiatives fail due to inadequate consideration of the cultural variables involved, including the CVF into the strategic planning process should greatly increase the chances of success. Through clearly defined steps, the CVF can help realign the organizational culture to match the new strategic focus, from the individual manager to the entire organization, and then on to the world.

About the Author

Scott Lincoln is a management professor at Handong Global University in Pohang, South Korea. He holds an MBA from Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business and is a Ph.D. candidate in Regent University’s Ph.D. in Organizational Leadership program.

Email: slincoln@handong.edu

About Regent University

About Regent

Founded in 1977, Regent University is America’s premier Christian university with more than 11,000 students studying on its 70-acre campus in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and online around the world. The university offers associate, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in more than 150 areas of study including business, communication and the arts, counseling, cybersecurity, divinity, education, government, law, leadership, nursing, healthcare, and psychology. Regent University is ranked the #1 Best Accredited Online College in the United States (Study.com, 2020), the #1 Safest College Campus in Virginia (YourLocalSecurity, 2021), and the #1 Best Online Bachelor’s Program in Virginia for 13 years in a row (U.S. News & World Report, 2025).

About the School of Business & Leadership

The School of Business & Leadership is a Gold Winner – Best Business School and Best MBA Program by Coastal Virginia Magazine. The school also has earned a top-five ranking by U.S. News & World Report for its online MBA and online graduate business (non-MBA) programs. The school offers both online and on-campus degrees including Master of Business Administration, M.S. in Accounting (Tax or Financial Reporting & Assurance), M.S. in Business Analytics, M.A. in Organizational Leadership, Ph.D. in Organizational Leadership, and Doctor of Strategic Leadership.

References

Belasen, A., & Frank, N. (2008). Competing values leadership: Quadrant roles and personality traits. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(2), 127-143.

Boje, D. M. (1991). The storytelling organization: A study of story performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(1), 106-126.

Bullis, C., Boal, K. B., & Phillips, R. (1993). The impact of leader behavioral complexity on organizational performance. Proceedings of the Southern Management Association (pp. 197-199). Atlanta, GA.

Cameron, K. S., & Freeman, S. J. (1991). Cultural congruence, strength and type: Relationships to effectiveness. Research in Organizational Change and Development, 5, 23-58.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cameron, K. S., Quinn, R. E., DeGraff, J., & Thakor, A. V. (2006). Competing values leadership: Creating value in organizations. London: Edward Elgar.

Denison, D. R., Hooijberg, R., & Quinn, R. E. (1995). Paradox and performance: Toward a theory of behavioral complexity in managerial leadership. Organization Science, 6(5), 524-540.

Denison, D. R., & Spreitzer, G. M. (1991). Organizational culture and organizational development: A competing values approach. In R. W. Woodman & W. A. Pasmore (Eds.), Research in organizational change and development (Vol. 5, pp. 1-21). Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Gregory, B., Harris, S., Armenakis, A., & Shook, C. (2009). Organizational culture and effectiveness: A study of values, attitudes, and organizational outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), 673-679.

Hart, S. L., & Quinn, R. E. (1993). Roles executives play: CEOs, behavioral complexity, and firm performance. Human Relations, 46(5), 543-574.

Hooijberg, R. (1996). A multidirectional approach toward leadership: An extension of the concept of behavioral complexity. Human Relations, 49(7), 917-947.

Hooijberg, R., & Petrock, F. (1993). On cultural change: Using the competing values framework to help leaders execute a transformational strategy. Human Resource Management, 32(1), 29-50. House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. London: Sage. Hughes, R. L., & Beatty, K. C. (2005). Becoming a strategic leader: Your role in your organization’s enduring success. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kluyver, C. A., & Pearce, J. A. (2006). Strategy: A view from the top. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Lawrence, K., Lenk, P., & Quinn, R. (2009). Behavioral complexity in leadership: The psychometric properties of a new instrument to measure behavioral repertoire. Leadership Quarterly, 20(2), 87-102.

Quinn, R. E., & Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science, 29, 363-377.

Schein, E. H. (1985). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Tsui, A. S. (1984). A role set analysis of managerial reputation. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 34, 64−96. Weick, K. E. (2003). Positive organizing and organizational tragedy. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (p. 72). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Zafft, C., Adams, S., & Matkin, G.. (2009). Measuring leadership in self-managed teams using the competing values framework. Journal of Engineering Education, 98(3), 273-282.