| How often have you looked back on a past event and thought; "if I knew then what I know now, I could have . . ." When we consider a past event with the advantage of reflective hindsight, we generally find areas where we would have made better decisions. Unfortunately however, until someone finds a way to break free of the space-time continuum, going back in time and reworking past decisions is an exercise in could-a, would-a, should-a. But what if, rather than going back in time to fix a poor decision, you were able to look forward in time; and with this foresight you were better prepared to take advantage of a particular event or better equipped to deal with a difficult circumstance. While strategic planning is a vital competency for today's leaders as they craft a vision for the future, an equally important leadership competency is strategic foresight to anticipate how this future might unfold.

Strategic Vision & Strategic Foresight

While subtle, there is a distinction between vision and foresight. Bill Barton, former center head for American Express' Consumer Lending Operations, helped me understand this distinction in this way: "It was vision that inspired the invention of the automobile. It was foresight that anticipated traffic jams, accidents and pollution."

In a more academic sense, strategic vision might best be described as both the a) formulation of emerging themes, issues, patterns and opportunities through the intuitive and creative exploration of external influences (e.g. environment, resources and competitive landscape) (Sanders, p. 162) and b) the formal composition of "distinct steps, each delineated by checklists and supported by techniques" for "implementation through detailed attention to objectives, budgets, programs and operating plans" (Mintzberg, p. 58) .

In contrast, strategic foresight concentrates on anticipating those forces that may come into play to assist and/or detract from a desired outcome. Unfortunately, there is often the misperception that foresight entails predicting or envisioning future events. Slaughter, in his book The Foresight Principle , helps counter this misperception when he writes: "foresight is not the ability to predict the future. It is a human attribute that allows us to weigh up pros and cons, to evaluate different courses of action and to invest possible futures" (p. 1) . To this end, Slaughter suggests that the process of strategic foresight encompasses broadening our perceptions of what future possibilities may unfold and therefore, considering various situations beyond our normal line of sight (p. 48) .

Why Strategic Foresight?

If we were honest, most of us would confess at least a casual curiosity for what the future holds. And we're not alone. Anecdotally, Barnett and Johnson observe that over one billion people turn to "astrology or other aspects of divination" for a glimpse into the future (p. 845) . Still, there is scientific evidence that as humans, we are driven to want to know the future. According to neurobiologists, Drs. Calvin and Ingvar, the human brain is hardwired in its drive to envision and plan for future events. Unlike other animals whose planning is hormonal and driven by seasonal patterns, the human brain is "capable of planning decades ahead, able to take account of extraordinary contingencies far more irregular than the seasons" (Schwartz, p. 31) . But recall that contrary to predicting the future, strategic foresight centers on the principle of "backcasting" from an anticipated future, back to the present, using both scientific and intuitive techniques and frameworks (Marsh) .

So why do leaders need to be concerned with strategic foresight? Because without foresight, we are apt to steer into the future blindly; unable to visualize the total picture and the possible consequences of our actions or inactions (Slaughter, p. 3) . We see the outcome of poor strategic foresight everyday at that crazy intersection we navigate while holding our breath and praying fervently. We complain that a traffic signal would certainly solve the problem and mumble to ourselves that nothing will happen until a serious accident occurs. Then a serious accident does happen and the next thing you know, a traffic light shows up.

Slaughter provides another compelling account of poor strategic foresight when he chronicles the identification, discussion and eventual after-action plans designed to deal with CfCs erosion of the earth's ozone (p. 52). While global leaders finally put plans into action to deal with the depleting ozone, "it took 13 years from the first scientific paper to the signing of the Montreal protocol" to find tangible traction on this critical issue (Slaughter, p. 52).

How to Develop your Foresight Competency: Scenario Planning

If we consider strategic foresight a critical leadership competency, how does a leader develop and refine this skill? One technique for enhancing your strategic foresight is to engage in regular scenario planning - outlining two or three potential futures with various possibilities and rehearsing how you might respond to each scenario; much like you might do when playing chess. But, unlike chess where you might memorize various moves and countermoves, in scenario planning, memorizing Plan A and Plan B is futile; "because in the real world A and B overlap and recombine in unexpected ways. (Thus scenario planning) is a matter of training yourself to think through how things might happen that you might otherwise dismiss - to get to know the shape of unfolding reality. To have at hand the answer to the question: 'What if.?'" (Schwartz, p. 30) . To this end, scenario planning enables us to understand how the future might unfold as a result of our decisions as well as external influencers. Thus, the development of a trend, a strategy or a wild-card event may be described in a scenario of possible futures ( The Art of Foresight , pp. 4-5) , to which the following steps are involved:

- Understanding where you are today and assessing the implications of present actions and decisions (Slaughter, p. 48)

- Outlining possible future events which would include both favorable, unfavorable and status-quo scenarios (Slaughter, p. 48)

- Establishing markers within your plans to help indicate which scenario might be unfolding (Schwartz. p. 199)

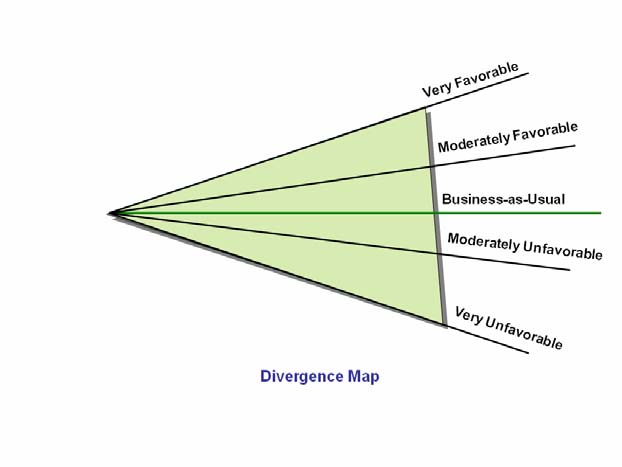

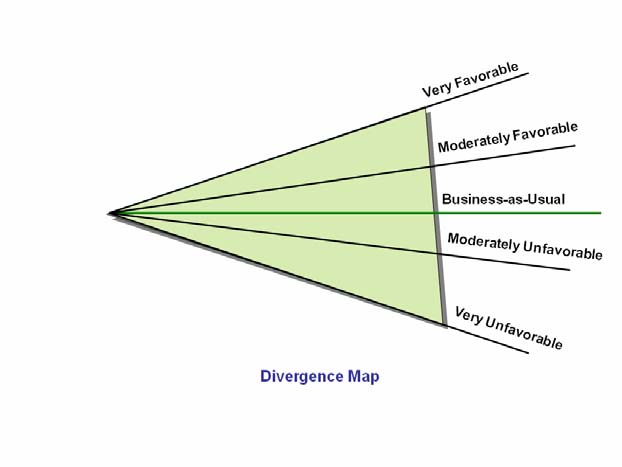

A visual that may assist in your scenario planning is a divergence map. The divergence map helps you chart out various future aspects against your present position by measuring favorable and unfavorable scenarios against your business-as-usual course of action (e.g. business-as-usual). Figure 1 is a sample divergence map. In this map "unfavorable scenarios" would reflect conditions where critical events went awry while "favorable scenarios" reflects conditions where breakthrough events occurred. The green "business-as-usual" line reflects anticipated conditions if current policies/strategies play out (Slaughter, pp. 75-77).

Figure 1: Sample Divergence Map

There are two key points to keep in mind when developing your divergence map. First, it can be a great aid in scenario planning to identify several markers within each scenario that can serve to highlight which plan is playing out. For example, in the 80's, Shell Oil projected that the Soviet Union might very well succumb to a failing economy and turn to a free-market system. Within this scenario, Shell identified several markers that might signal such a move. One marker was Gorbachev coming into power; another marker was that Gorbachev would identify Agenbegyan as Moscow's chief economic advisor. While Shell had outlined other markers along this scenario which did not unfold, enough markers were hit to give Shell a strong sense that indeed the free-market scenario was playing out in the Soviet Union (Schwartz, pp. 205-208) .

The second point to keep in mind with divergence maps and scenario planning is to avoid fixating on one scenario. Author Peter Schwartz cautions that when planning scenarios "there is an almost irresistible temptation to choose one scenario over the other(s): to say in effect, 'this is the future which we believe will take place'" (p. 203). Focusing attention on one scenario can blind the leader to other scenarios which might be unfolding because of a bias towards a given outcome.

The Starting Point: Organizational Myths & Cultural Change

In starting your scenario planning, Schwartz outlines several steps that can help leaders build robust plans (pp. 226-232):

• Identify a focal issue and then build outward toward that position (e.g. begin with the end-state in mind).

• Outline those forces that can influence the outcome of the scenario (e.g. customers, suppliers, technology, political, etc).

• Review those forces that are most important to a scenario and those that are most uncertain. This will allow the leader to identify those factors that are most critical and distinguishable in impacting a scenario.

A key tenet of scenario planning is that every future scenario will begin with cultural change, either societal, organizational or both (Schultz, p. 28) . Often, technical advances will drive these changes, such as seen with the advance of personal computers or breakthroughs in healthcare. However, cultural changes may come about as a result of societal influences as well (consider the impact of air travel post 9/11). As you begin your scenario planning, it will be important to consider how your organizational culture might evolve (either by design or by necessity) as you move into the future.

In this regard, a helpful place to start in scenario planning is to reflect on those organizational myths that define the character and behavior of your company. All organizations have myths (stories) about their past accomplishments and defeats. These myths reinforce an organization's perception of "the way they are" and reflect a pattern of behavior, perception or belief of the organization's values and culture (Schwart, p. 44) .

Here's an interesting exercise to help you reflect on the impact of myths in your organization. The next time you hear someone recount a story from your organization's past, pause and reflect how the organization's culture is reinforced. For example, if your organization sees itself as innovative with out-of-the-box thinkers, odds are stories will circulate that highlight this belief. The same is true if your organization has a myth of "missing the big picture," stories will undoubtedly surface that point to lost opportunities or dropped balls.

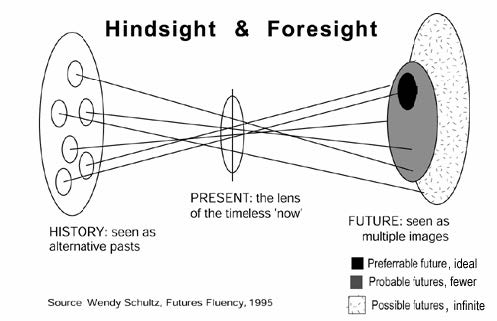

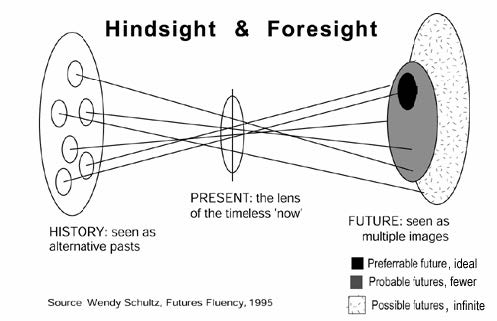

In themselves, these myths are not consciously fictitious (Schwartz, p. 44) . Myths may indeed be grounded in fact. However, the further back the time associated with the myth, the more likely the myth departs from truth. Just as there are infinite possible futures, there are "infinite alternative pasts, which compress (in accuracy) as they approach the interval of the present" (Schultz, p. 30) . In Figure 2, Schultz helps us visualize how both hindsight and foresight each reflect alternative past as well as possible futures. Thus, a critical aspect of a leader's strategic foresight skills will be to communicate and live a set of core values that inspire and motivate people to follow (Tichy, pp. 274-275) while engaging the foresight to analyze potential future scenarios and the wisdom to know how to maintain as well as change those values that will enable success (Tichy. pp. 173-175) . However, when advocating cultural change; caution is the better part of valor because this type of change is akin to a spiritual formation. It is important to know going in that not everyone will be on board with cultural changes at the same time.

Figure 2: Hindsight & Foresight

Global and Organizational Influences

Finally, in building your scenario plans, it will be helpful to consider the impact of global and organizational influences. For example, global leaders who are organizationally savvy are not only able to recognize market opportunities, but are able to leverage the resources of their organizations to capitalize on these opportunities (Black, p. 149) . This is accomplished by mastering the dynamics of "duality" (the pressures of global integration and local adaptation) (Black, p. 26) and "dispersion" (the degree to which resources are distributed within a worldwide organization) (Black, p. 25). Effective global leaders build and maintain organizational savvy first and foremost by getting close to their customers (Black, p. 159). Additionally, tactical proficiency is developed in their international understanding of finance, accounting, marketing, etc. (Black, p. 156). Thus, teaching leaders "how the business works, (enables) business-literate leaders (to) build cultures of learning and innovation" (Rosen, p. 136) . When building your scenario plans, carefully assess the capability of your organization's global leadership. Specifically, does your organization's global leaders, in relation their ability, 1) "confront and overcome" conflicts in the marketplace and 2) have the "capacity to manage uncertainty (and) . . .the ability to balance tensions" (Black, pp. 78-79)?

It will be helpful to likewise assess your organization's inclination to tolerate risk. Uncertainty avoidance is the natural inclination to plan, predict and anticipate as many of life's uncertainties as possible so as to avoid undue anxiety and stress. However, uncertainty avoidance should not be confused with risk avoidance. While individuals may want to manage events to prevent unpleasant surprises, these same individuals will willingly engage thoughtful calculated plans which may have a less than 100% probability of success (Hofstede, pp. 145-149) .

To help manage through uncertainty, successful leaders exhibit the following characteristics (Black, pp. 83-86):

• Master environmental complexities by moving forward with confidence and determination; even without clear direction

• Apply the 80/20 rule by leveraging what is known to the situation at hand and allowing the unknown to be discovered and addressed along the journey

• In uncertain times, look to pattern direction based on industry best practices and benchmarking

According to Black, Morrison and Gregersen, "inquisitiveness is the fundamental driving force behind global leadership success," because in the face of uncertainty, inquisitiveness not only helps global leaders seek out useful and timely data, it helps them sort out and make sense of that data. Global leaders know that inquisitiveness is the only prescription for uncertainty when facing a mountain of inconsistent information" (Black, pp. 42-43). McCall and Hollenbeck echo this point when they suggest that "talent, or more precisely, potential, can be viewed as the ability to learn from experience (p. 6) .

Summary

While strategic visioning continues to be a leadership challenge, Lombardo and Eichinger provide a compelling summary on the challenges associated with strategic foresight when they write:

"There are a lot more people who can take a hill than there are people who can accurately predict which hill it would be best to take. There are more people good at producing results in the short term than there are visionary strategists. It is more likely that (an) organization will be out maneuvered strategically than that it will be out produced tactically. Most organizations do pretty well what they do today. It's what they need to do tomorrow, that's the missing skill" (p. 346) .

Today's leaders commit significant energy building compelling strategic visions to inspire and guide their organizations into the future. But without the ability to anticipate how this future might unfold, some leaders may find themselves unprepared to deal with the future they've led their organizations toward. While strategic vision will help a leader plan for the future, strategic foresight will enable a leader to deal with the inevitable variations that will occur as that future unfolds. Thus, while our vision will always denote an image of the preferred, idealistic future, our scenario planning will outline those possible alternative images the future may hold. Given the uncertainty for these alternative future images, leaders would do well to add strategic foresight to their toolkit.

Marsh, McAllum and Purcell encapsulate this thought when they write:

"When we truly 'stand in the future' we are able to create a view that is unrestricted by the present. We are free to create scenarios of possibility and understanding. We are free to realize that the future is not predetermined, something that we have to react to and cope with - but rather that it offers a range of possibilities, depending on our responses now to those possibilities" (Marsh) .

|

References

(2004). The art of foresight . Bethesda: World Future Society.

Barrett, D., & Johnson, T. (2001). World Christian trends . William Carey Library.

Black, J., Morrison, A., & Gregersen, H. (1999). Global explorers . New York: Routledge.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequence . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Lombardo, M., & Eichinger, R. (2000). For your information . Minneapolis: Lominger Limited.

Marsh, N., & McAllum, M. (2002). Strategic foresight: The power of standing in the future . Crown Content, Australia.

McCall, M., & Hollenbeck, G. (2002). Developing global executives . Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., & Lampel, J. (1998). Strategy safari . New York: The Free Press.

Rosen, R. (2000). Global literacies . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sanders, I. (1998). Strategic thinking and the new science . New York: The Free Press.

Schultz, W. (1995). "Futures fluency: Explorations in leadership, vision and creativity." University of Hawaii.

Schwartz, P. (1991). The art of the long view . New York: Doubleday Currency.

Slaughter, R. (1995). The foresight principle . Westport: Praeger.

Tichy, N., & Devanna, M. (1990). The transformational leader . New York: John Wiley & Sons.

|